Our Southern Garden Gave Us Rich Memories

It was high dusk on a gray November day. We had countless plants we’d collected on the fly from our thirty-five-year-old garden tightly wedged into the back seat of the car. There was no looking back as we drove off to our new home in New Hampshire. We had already brushed vestiges of mud from our clothes.

The mud had not come, as you would suspect, from a wistful farewell ramble through garden beds we would never see again. The leavetaking was much too hectic for such leisure. It came from the mundane – and muddy — task of trying to read a drowned water meter. This was a final, futile favor to a county water department that had occasionally been generous to us when we left our hoses running through a summer night.

Now, the paths, the steps, the open space, the beds and borders, the woodlands, and all creatures who lived among them would be cast behind to awaken only in memories and old photos, some reproduced here in slide shows.

The Garden We Were Leaving

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Faithful Ranger, not the garden, got the last formal goodbye. After three decades of reliable service, we were giving our ’92 Ford truck to our magician-mechanic in hopes that he would find a good home for it. Now, during this last stop, we were turning the title over to him. We gave him one last hug, and with a quick pat to Ranger’s fender we took leave.

Ranger had hauled peanut hulls, cotton dirt, manure, mulch, sand, bricks, landscape ties, fence posts, shingles, lumber and garden trash, and he had plucked stubborn, storm-damaged plants from garden beds with the pulling power of his six-cylinder engine. There probably wouldn’t have been a garden without Ranger.

There Will Never Be Another Ranger

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Our garden had grown into a bunch of rambunctious, wayward, tumbling rowdies, always threatening to spin out of control. Each year, I vowed would be the year the garden would shape up. That never happened, of course, as plants have a way of growing out of bounds in southern summers.

So we settled into rationalizing that the garden was a work in progress that bugs and people liked, one grand experiment. Bob called it The Jungle.

Mind you, I was forever transplanting and re-organizing, rescuing the timid from thugs, removing innocents caught in the way of my current new wave (a touch of idiocy?), and taming upstarts that hadn’t read the books. But that wistful eye for just another new plant, like wondering what’s around the bend in the road, kept me in a pickle pail full of delightful discoveries, including, outrageously, a Dawn Redwood that eventually shared the skies with oak and maple.

So spirea nudged azalea. kerria tangled with sinocalycanthus. Clematis ‘Nelly Moser’ lounged on ‘Fashion’ azaleas. The tendrils of sweet autumn clematis tried mightily to reach out and embrace the entire garden. Summer natives danced out of bounds. Grasses kissed the sun. And we took pleasure in the tangle.

Lovely Rowdies

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

During the final rolling weeks of packing, plants had become the last things on my mind. Earlier, they had been first priority. So many had been propagated here, they were like a second family. I dug up whatever I thought would survive the move North and, graciously, Steven and Susan transported and cared for my potted addictions (except for last-minute smuggles noted above).

There were not as many as I thought. I’d spent years of hankering after one of those perfect New England gardens featured in glossy magazines only to find that the plants inevitably succumbed to southern heat, humidity and mucky soil. Finally, I had learned the limits of my space and I grew to love the lush growth and lavish parade of bloom that came with these southerly tough/tender plants.

Now that we were moving North, I was saying goodbye to plants I would not soon meet again: camellias, Florida anise, abelias, southern azaleas, and most of my hydrangeas. And especially that grand watermelon crepe myrtle strung with Spanish moss that transformed our modest front lawn into a cliched but gracious southern landscape.

Southern Plants I am Missing Already

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

It wasn’t just plants I was saying good bye to. Years back I came to gardening with a scrubbed face and shining eyes and lots of book-knowledge. I thought I knew it all. Yessiree, I would build beds and borders just right, perfect, with plants that behaved. I had the ultimate Grand Plan.

Then people started giving me plants. I was touched and delighted. But, horrors, their plants were not part of my Grand Plan. Oh dear! Where do I put a plant that is not part of the Grand Plan?

I needn’t have worried. In those first years we had no idea of how to garden in gray clay that dried to pottery shards, so most of my Grand Plans fizzled. I welcomed gifts from knowledgeable gardeners. As I watched the plants grow and bloom, they evoked sweet memories of good friends.

I learned that a garden is a tapestry tight-wove of plants and people and remembrance of good times past. Like the lingering sweet smells of blossoms on a moonlit summer night, memories of people who loved plants, walks and talks with them, visits from Master Gardeners, plant sale days, faux barbecues on the gazebo, even making quince jam, gifts given and received, would fill my spirit as I brushed by familiar plants.

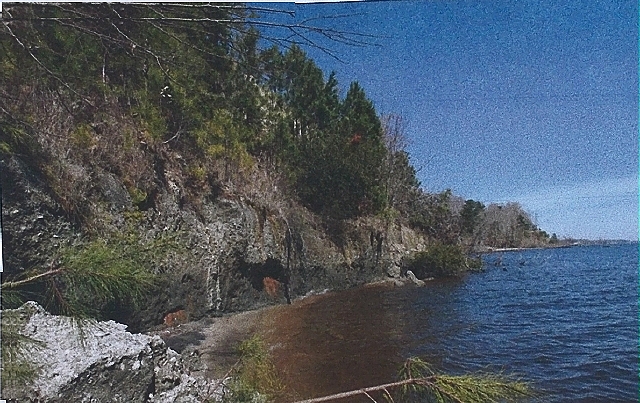

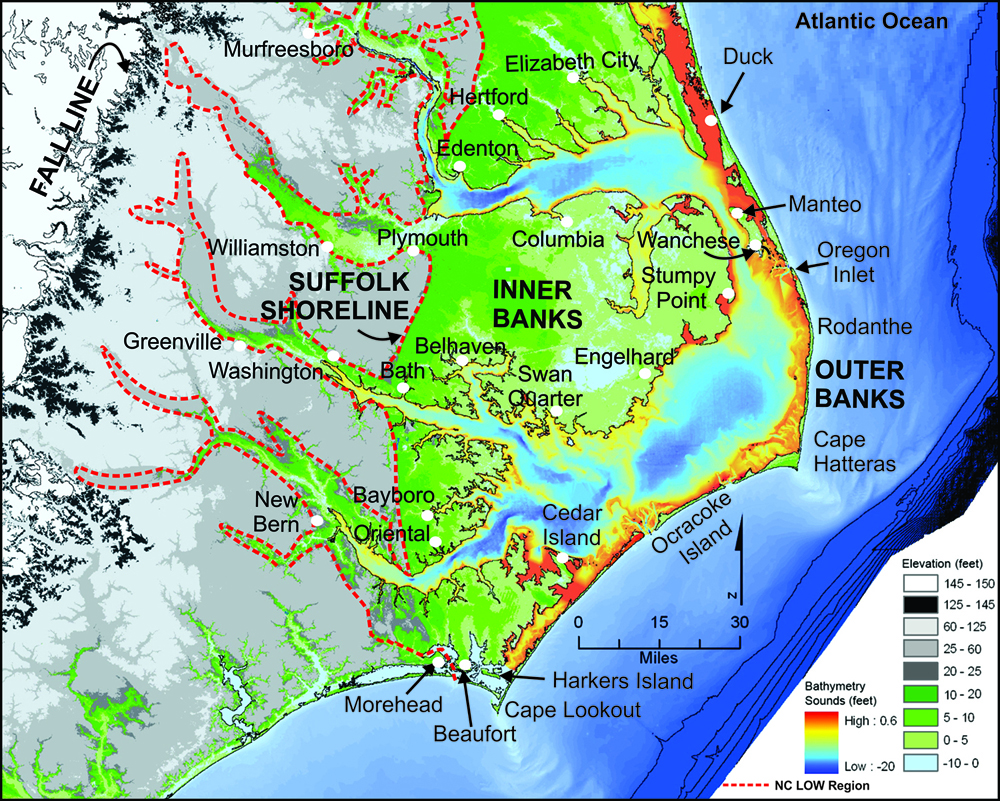

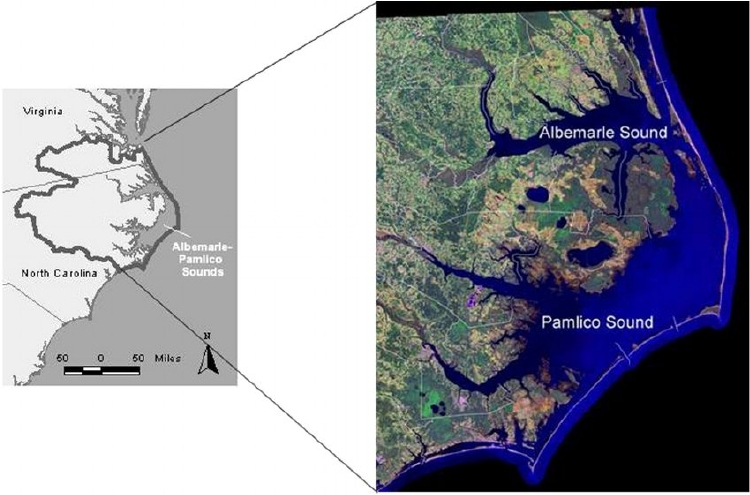

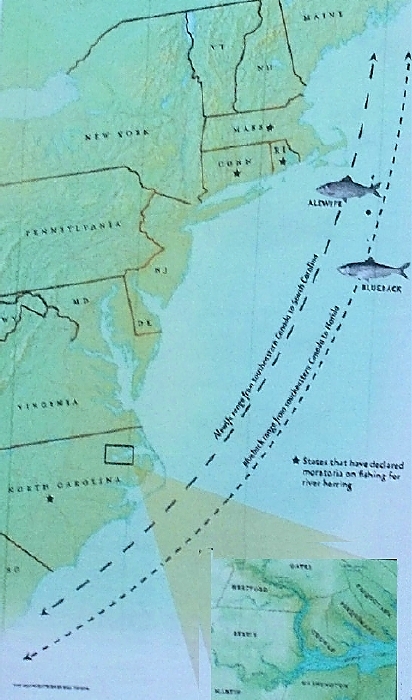

And I will never forget the peace that wrapped itself around one and all as we roamed the paths or relaxed in the gazebo. I can still hear the quiet swish of breezes and wavelets off Albemarle Sound that once lulled us into golden hours, remote from the clutter of everyday life.

Now the memories belong to me, but the plants belong to others.

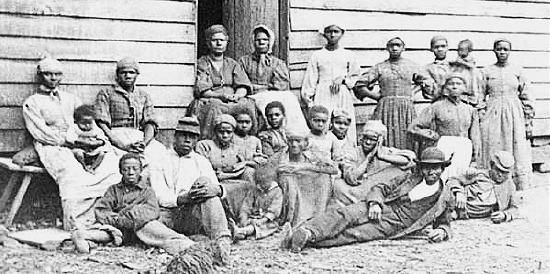

People in the Garden

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

I had never set out to create a garden for butterflies, or birds, or other animals. I simply collected lots of plants that I liked, and tossed them together into a smorgasbord with woodlands. And life came out of the shadows and into my garden. Swamp red bay (already on the property) and spice bush (purchased as sprigs) attracted swallowtails.

Blue mist flower was a siren that drew every sipping insect with wings, and slender black wasps loved clethra. Wild honeybees gossiped in abelia grandiflora until mites invaded hives and silenced the happy spring buzz. Argioppe spiders, relatives of wise Charlotte who crafted messages in her web, crafted their own messages to lure end-of-summer prey.

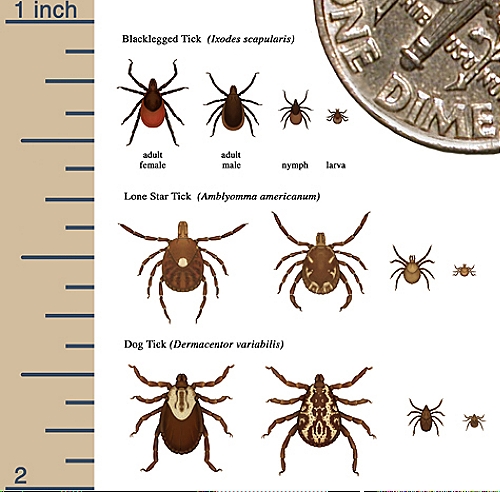

As to the unwanted, chiggers and ticks and mosquitos, well, we managed, occasionally having the garden sprayed professionally with garlic and essential oils. There might be holes in some leaves, but mostly the garden remained healthy, possibly because we were faithful about adding compost that nourished plants and erratic about using chemical fertilizers. Camellia tea scale was the only insect we treated with oil spray once or twice a year.

The Small Critters We Loved

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Come warm sunny days in February I’d be poking around, impatient for new life. If plants weren’t risen and happy I would fret. But with the February sun came the first tentative warblings of newly awakened birds and my spirit would quicken. Territorial stake-outs and mating would lead to summer adventures.

Mockingbirds claimed exclusive rights to elderberries. Baby titmice prattled in baskets of ferns. Cardinals fought their reflections in windows. Woodpeckers woke us, banging on metal drain gutters.

Carolina wrens regularly invaded our garage scouting for nesting niches. Hummingbirds buzzed indignantly when the feeder was empty. During a droughty year a woodcock visited our sparsely watered garden to seek worms nearer the surface than in the dry woods. And, through dusky woodlands, a wood thrush would send us a summer aria.

One year a cowbird deposited her eggs in the nest of a prothonatary warbler. How disappointing to see baby cowbirds instead of baby warblers!

One spring a black snake took up residence in the bluebird box just as the babes were ready to fledge, traumatic for us and the family, and for the local bird population who flew in to – well, we are not sure why. Watch the action? Express outrage? Render vocal support? Get first dibs on an empty birdhouse?

Bob turned the box upside down and banged it until the stubborn snake apparently got addled. As it tried to slither away, he caught it and took it to a distant patch of woods while the birds were reunited. Amazingly, all but one nestling fledged.

Osprey keened when the amelanchier bloomed. And the great blue heron would stop by in summer for fishing and loafing, along with the turtles. One year, when we were cleaning the pond, he skulked behind shrubs and trees, homing in on vulnerable fish. We were on to his tricks but he knew when we were watching and he figured out how to win.

Winter, plants stripped of frippery, would reveal the housekeeping of summer’s smaller tenants: messy, casual, accomplished. Then February would come round again and we’d see the lone pied billed grebe cavorting in our slip and hear the first warblings that heralded a new spring.

Heron and Friends

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Sometimes, when I puttered during quiet summer evenings, potting or transplanting, a young squirrel, or a solo rabbit would follow me around, so close behind I would have to watch where I stepped. These young critters, recently graduated from cozy nests, seemed to want company, any company. I enjoyed their presence and would murmur nothing-phrases to them as I moved through the garden, though I was happy when they grew into independence.

One summer a frisky fawn latched on to me, one of twins introduced to us on a sunny afternoon by the doe herself. He’d watch me while I gardened, waiting for me to chase him. When I turned round to scold, the game began. One day I found him devouring an entire vine, tendrils dripping deliciously from his mouth. I stood quietly until he finally noticed me. One long moment of indecision, then, with great reluctance, he dropped the vine and took off before I could scold him.

Creatures came and went. There was a part of the property we rarely visited, left it to wildlife. A pair of coyotes camped out for a couple of years, skinny, almost gaunt. I know because I came face to face with one as we crossed paths. I took a silent breath. We stood motionless, both vulnerable, sizing each other up. I dared not turn my back. The coyote, braver, finally turned away and loped off.

Then there was the blind raccoon who hung around for a few weeks and scared a young possum away by accidentally bumping his nose. And the semi-tame rabbit from two properties down who wandered to our place regularly, following us as we worked. And the otters who played on our dock one summer. And the beaver who must have had delusions of grandeur thinking he could gnaw down a forest of mighty sweet gum trees.

The crayfish that were always building castles in clay undermined our paths, but we never managed to spot one. For a while a groundhog was resident, but during a rainy year he left after his underground digs turned muddy. We had tried to catch him but only snagged a baby raccoon, whose mother, distraught, left the grounds permanently, trust broken, even after we freed her youngster.

There was always a frog singing in the pond. One summer we swore he sang to us, since he was quiet until we came round and spoke. Occasionally a fox showed up but we never found a den. And once there was bobcat scat in a planter box, but we never saw the bobcat.

The Bigger Critters

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

If Ranger was the workhorse on wheels, Bob was the builder who quietly did what needed to be done outside, and that is probably my fondest memory of all. Bob gave the garden its structure: gazebo, shed, decks, dock, steps, fences, brick edging for beds, crooked paths with steps, an automatic watering system, and the courtyard off the garage. Sometimes he worked solo; sometimes friends joined him.

Any bright new idea I had he was willing to tackle, transferring my sketchy thoughts with deliberation and a Number Two pencil onto graph paper, until he converted ideas into reality. Our first project, a challenge, was laying brick for a sinuous wall under our large south-facing den windows.

Most years there was damage from storms and Bob would be out lopping and pruning and sawing, sometimes felling entire trees while I held my breath. These were probably his favorite projects. A man and his chain saw. . .

And his chipper-shredder. We would rake and he would shred leaves and branches to make instant mulch, some of which eventually became velvet soil. As trees grew taller, we’d be ankle-deep in leaves. But those leaves were clay-busters. After years of mulching, our soil finally became diggable.

Far less dramatic were my numerous requests to plant and transplant, so Bob made himself a distinctive Master Digger badge to wear during garden tours and plant sales. As he dug, he sent each plant on with a proviso: Don’t get too comfortable, he’d say, because you will probably get moved—again.

Oh, and Bob was good friends with Ranger.

Mr. Bob

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

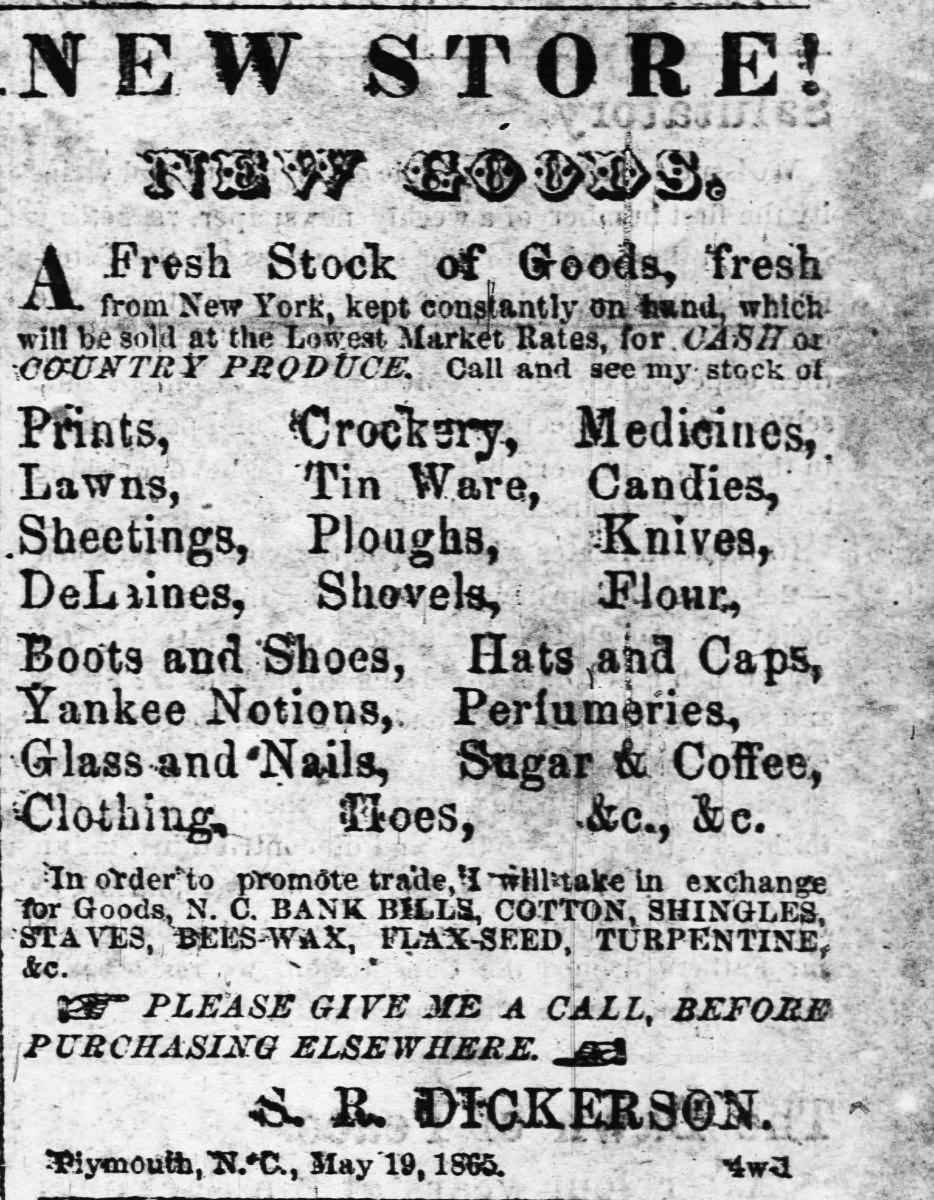

Three decades of my memories are seamed to the garden with a lock stitch that cannot unravel. Having tossed the rigid Grand Plans and planting for joy instead, I began collecting spectacular (to me) trophies with a sense of adventure and the zeal of a religious convert, haphazardly, from anywhere – weedy fields, abandoned gardens, rural mom-and-pop roadside offerings. If nobody was home we dropped our money in an honor box.

Often I tooled around country roads with a good friend scouring ditches and vacant fields we’d scouted previously (trespassing?) to gather samples of all sorts of interesting plants (weeds? No, natives.), always watching our backs for the muzzle of a shot gun as we dug.

Rose’s Department Store and the old K Mart had interesting plants, too, for practically pennies. . The crab apple in front of our house came from K Mart and was the first tree we planted that lived. It cost $8. It bloomed the first year.

Once we found dogwood saplings for a dollar a piece, but you had to buy ten to get the bargain. Ten dollars! Too much for our thrifty plant pocketbooks! So we divided them between us, and split the bill, and five dollars didn’t seem so outrageous. And yes, most of them lived!

Plants-by-mail were cheap, postage nickels and dimes. As we explored the coast, from Florida to Maine, I inveigled plants from specialty nurseries, motel managers, garden caretakers. Verges along country roads gave up some gems, too. The challenge was in the chase.

I confess today to owning a large wooden box dedicated to certain garden keepsakes: plant labels and price tags (which also remind me of how many I lost along the way).

But, oh my, when I learned how to propagate plants from tiny cuttings, that was the ultimate in plants for pennies. From a couple of purchased George Tabor azaleas I grew great swathes of blooming plants. Roadside plants contributed specimens, as did friends’ gardens, and other nameless gardens. Large carry-alls hid evidence of twig-rescues for a good cause. Each cutting that lived created a special memory.

So the garden grew from cuttings and clippings, and I began giving away plants until I noticed people avoiding me when I had a potted plant in hand. That was when we began holding annual plant sales and donating funds to environmental education.

Many of my trophies perished along the way. But many lived on, too, and those ragamuffin early days of plant hunting hooked me, even as plant prices rose and plants were often strait-jacketed in pots with pretty pictures.

In the beginning, I believed I was the guiding light in the process. But chastened by experience, my focus shifted from collecting to looking, really looking at my garden, absorbing the joys and disappointments as they came along.

On grand scale I rejoiced in a fairyland of dancing lights and shadows over the water on summer afternoons when the sun came in from the west. Then we would sadly clean up the mess when storms struck down the fairyland. On smaller scale, I took delight in blossoms lit by stray sunbeams that tarried after sunset. These picture-memories of fleeting visions I hold close.

Early Gardens and Plant Hunting and Propagation

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Each spring, we declared, was the best ever! Were we honing our gardening skills? Learning to grow better plants? Coping with clay? Had we become sorcerers? (Such preening!) No, the joie de vivre came not from us but from the timeless rhythms of nature. We were only her stewards seeking pleasure in her handiwork.

By mid-summer, the garden could look tired, with no relief from hot days and hot nights. Fall was a resurrection of sorts, as new blooms and berries and golden leaves shined up the garden. Snow in winter was a treat, though wet winters could send mud up to your ankles.

But spring was special because plants were just beginning to stretch out, not yet encroaching on each other. We could enjoy order and leisure and color in a fresh, dewy garden. Weeding and pruning and watering would come later. We could cheer the splendid parade beginning with camellias and on to magnolias, azaleas, clematis, flowering trees and hydrangeas.

Those Glorious Springs

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

The woods were a dark backdrop to the garden during those first few years. Only the trees around the house were cleared. Which goes to show what suburban slickers we were. In hurricane-prone country it is not a good idea to have trees hugging your house.

We built our house with more windows than walls, the better to see the garden and the woods year round, also trees coming down during storms. Our garden in the woods might never have tripled in size if Hurricane Isabel hadn’t taken away some 150 trees and brought us light for growing azaleas and daffodils, which then made way for a new generation of trees.

A third of the trees were doomed immediately, twisted and thrown by embedded tornados or pummeled savagely by winds up to 100 mph until they toppled. Others, seemingly unscathed, were damaged internally, susceptible to insects and disease. They succumbed over time.

Isabel also taught us that trees change, light changes, even soil changes over time. The garden that once was can never come back without persistent masterminding.

Above all, she taught us that trees rule. Thirty-five years ago they were bumptious teenagers, leafy, skinny, and expectant. But our woodland trees were tough and patient. They scrabbled, they elbowed, their roots tangled, embroidering a complex network of self-support. They created their own soil and they inched up to 80-foot towers without our really noticing.

They gave us cool shade and they whispered to us on breezy days, and we used their leaves for mulch. But trees are takers. There is no contest between trees and alien plantings. And no compassion. Trees win unless the gardener is attentive and patient and willing to lose some struggles. We did not know this when we began our journey.

These trees were not picture-book quality. Some appeared to be girdled and half rotten at the base, yet they carried on. One was hunchback. Many had lost big limbs, so they were scarred and misshapen.

The Grandfather Pine that overlooked the north edge of the property spent a couple of years dying before, too late, we noticed that its upper branches looked like pins in a pin cushion on a pole. Bark beetles had clogged its arteries. A few years after we took it down, termites were working on the remains, turning it to dust and returning it to the forest.

Would we have given up our trees? Given up those afternoon shafts of sunlight sliding among their trunks, washing them with crayola-crayon earthtones? Given up our glimpse into the lives of birds among their branches? Given up following the lives of our trees as they flourished or became vulnerable and declined? You, dear reader, can guess the answer.

Instead, we cleaned up messes from storms and soldiered on to create our Garden in the Woods. Despite some spectacular disappointments, we learned patience and wisdom and acceptance and how to get along with the trees that had become family.

A Garden in the Woods

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

I left a part of my heart in that North Carolina garden. Mostly I miss the light whispering through trees, kissing leaves, dropping diamonds on wavelets. One afternoon a visitor told me that he felt like he was in a fairyland, and that vision will stay with me for the rest of my life.

A clear resin suncatcher with memories pressed from our fall garden, gift from a talented neighbor, sparkles in the morning light that streams into my new kitchen. It makes me smile.

I wonder about the garden. Will the new owners be patient with the trees and the tangle? Will they be patient enough to wait for the ‘Near East’ crepe myrtle whip we planted in an oversized box of landscape timbers to rise and bloom? We renamed the tree Hope.

I guess the best way to say goodbye to a garden is to begin work on a new one. But please, allow me a few more memories of our thirty-five years in our eastern North Carolina landscape.

Some Final Memories

This slideshow requires JavaScript.