River of Death, Giver of Life

Of all the rivers that feed Albemarle Sound, the Roanoke is the mightiest. It is a restless river. It can be ruthless. Its temperament shifts with the cragginess of the land it scours.

During a 400-mile journey it slices through the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia, spills over Piedmont hills, then snakes leisurely onto the wide, flat coastal plain of eastern North Carolina until it reaches Albemarle Sound.

A scrappy Roanoke River as it reaches the Fall Line near Weldon where it will literally fall onto the coastal plain. The Nature Conservancy photo 2015

River of Death the Indians called it for the killing floods that came after rain and snow-melt in spring or deluge from tails of hurricanes in late summer. Yet, if we look beyond the destruction, we see that the Roanoke is a Giver of Life.

Bottomlands like these on the coastal plain can be seen from bridges along US Route 17 South as you approach the town of Williamston. US Fish and Wildlife photo

Rushing waters from upriver slow their course when they reach the coastal plain and blanket bottomland forests with alluvial soil and detritus. Tons of it. Remnants of old lives are gnawed and shredded by an invisible army of mud-dwellers, and detritus becomes the engine that jump starts life in this river that forged one of the greatest fisheries in the country.

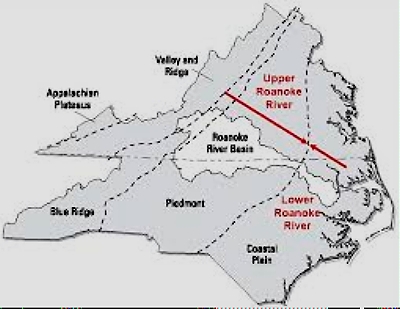

The North Carolina stretch of the Roanoke River and its basin from the Virginia/North Carolina border east to its terminus in the Albemarle Sound. Note the Fall Line near Weldon. The Roanoke follows a geologic pattern similar to other large rivers in the southeast. Map created by Elaine Roth

Roanoke River Basin showing boundaries of coastal plain, piedmont and mountains . Note that almost two-thirds of its drainage basin lies in Virginia

Vital Statistics

With a six-billion-gallon average daily flow, the Roanoke River carries more water than any other river in North Carolina. More than half of the fresh water in Albemarle Sound comes from the Roanoke. All told, the river and its tributaries drain almost 10,000 square miles of land in two states.

Rushing waters of the Dan River, a major tributary of the Roanoke, pictured above the Fall Line. Photo by Ken Taylor

The Fall Line near Weldon was a first frontier, a wall that kept ships from sailing up river, a barricade to an uncharted continent. Over a distance of only ten miles, there’s a dramatic 100-foot drop in terrain from the Piedmont to the Coastal Plain. This gateway to the Piedmont is punctuated by rocks, rapids and falls.

West of the Fall Line, the narrow hustling river cuts through gritty Blue-Ridge bedrock with 75-foot high bluffs flambuoyant with wild flowers in spring, then winds through channels of Piedmont hills. Below the rapids and falls, east of the Fall Line, the river bottom gentles out to soft sediments, crumbs of ancient mountains long ago eroded.

Here the river meanders through a flood plain as much as five miles wide with vast roadless swamps of baldcypress and tupelo-gum until it finds Albemarle Sound. These bottomlands, mostly still in tact, are larger than any found on the east coast today.

Aerial view of bottomlands and oxbows in the meandering river whose flood plain is thick with dense swamps. Albemarle Sound lies at the top of the picture

Wilderness bottomlands are actually a washboard of ridges and sloughs created by the constantly changing river. Sloughs (low areas, pronounced slews) are ancient river channels; ridges are natural levees formed during floods. Old growth forests of pine, oak and beech grow along these ridges.

Cross section of washboard bottomlands topography showing specialized habitats for plants and animals. From Roanoke River Profile by Albemarle Environmental Assn

Devil’s Gut is a real-life example of bottomlands topography. It lies north of US 64 between Jamesville and Williamston. It is a canoeist’s paradise.

This is untouched territory, no recent clearcutting, no ditching, no draining. It is primeval habitat with a wealth of wildlife:

A wilderness camper’s paradise. Tent platform nestled among bald cypress, one of several stopovers in the bottomlands for kayakers. Roanoke River Partners project and photo

An Eden for Wildlife

An incredible diversity of plant and animal life flourishes here, over 200 species of birds alone. A birder’s paradise.

Prothonotary warbler, often called the swamp canary, a year-round resident, is preparing to add moss to his nest in a tree cavity. Roads End Naturalist photo

Dense populations of white-tailed deer roam the ridges of the bottomlands.

As do wild turkey. Once abundant across the state, decimated by market-hunting and land-clearing, they are now thriving. Roanoke River turkeys, barely affected by market forces, became breeding stock that jump-started populations across the state.

Remote bottomlands protected the wild turkey from harvest while numbers dwindled across the state. NC Wildlife Resources Commission photo

The largest inland heron rookery in North Carolina is here in these remote wetlands. Great blue heron, great egret, and anhinga share nesting space, though not necessarily housekeeping duties. as any visitor can attest.

During the fall over 500 migrating hawks have been observed on a single day. Bald eagles make their homes here, as does the anhinga who prefers cypress swamps.

Anhinga fly-by. Its nickname is “snake bird” because only its long slender neck is exposed when swimming. Photo by Roads End Naturalist

Wetlands here are among the finest breeding and wintering areas for Wood Duck in North Carolina. Mallard and black duck enjoy loafing during the winter.

Another success story: black bear numbers have recovered since their lows during the mid-1900s. In remote Roanoke bottomlands, with space and solitude, ample food and mild climate, their adult size is impressive: they are the largest on the east coast. (This distinction is shared with neighboring populations on the Albemarle-Pamlico Peninsula and Alligator River.)

Black bear have been known to fatten themselves on campers’ food stashes, too. NC Wildlife Resources Commission photo

Beginnings

Less than a century after explorer Ralph Lane was lured up river in 1586 by tall tales of mountains of gold, then foiled by swift currents and hostile Indians, early settlers were drawn to this land of rich alluvial soil spread out beyond the banks of the Roanoke.

Lumberjacks, aptly named swampers, logged the rich black land along the river, clearing the way for folks with royal grants to create farms and eventually plantations.

These second growth tupelo and cypress trees give some idea of the magnificent forests that were being logged. After logging, ditching and draining would take place, a laborious effort that eventually deprived the soil of its fertility. aheronsgarden.com

Farmers and Planters

Farms of early settlers were small, 660 acres was the maximum land grant from the Crown, though there were invariably ways to get around this restriction. Rich soil and mild climate meant bountiful subsistence harvests, at least as long as soils remained fertile. Hunting and fishing provided protein, as did hogs and cattle.

Whatever was not needed would be sold or bartered, but with little access to distant markets, brisk trade with other states or the West Indies was slow to develop.

Lands with poor soil were owned by poor people. The best lands were held by the wealthy who increased their holdings and became plantation owners with slaves. They grew profitable crops for export to Europe: cotton, tobacco, and sugar, but especially cotton.

Cotton spelled cash during antebellum years and beyond. England and New England were expanding textile mills and the cotton gin (1794) spurred even greater production and healthy profits for southern growers and northern mills. Plantations along the Roanoke were considered among the finest in the east.

An 1890 photograph of a sharecropper family picking cotton. Bolls open throughout the season so picking would be done in waves, unlike today when chemical aerosols cause bolls of hybridized cotton to open simultaneously in fall

Powered by slave labor, antebellum decades became the golden age in the Albemarle area. Slaves worked the plantations and fisheries and built dikes to hold back floods. Exports of cotton, fish and naval stores primed the plantation economy.

Settlements like Plymouth and Williamston became leading ports and centers for entertainment when showboats arrived. It was not unusual for fifty or more ships to be docked at town wharves, loading shingles and barrel staves, cotton and salt herring.

The fine brick Grace Episcopal Church in Plymouth, built in 1837, gives some idea of the area’s prosperity two centuries ago. Photo by Jeanette Runyon

Other settlements, like Dymond City, Hog Town and Dalys Hill, now forgotten ghosts, flourished along a busy river. But high times along the river would eventually end. Settlers were too efficient at reining the Roanoke. Had floodwaters been allowed to encroach at intervals, soils would have been renewed naturally. Instead, as they became depleted, stakeholders moved westward to new territory.

A Canal and a Railroad

A sleepy settlement called Weldon’s Apple Orchard near the The Fall Line would soon become a transportation hub that linked the interior with the coast when neither fish nor ship could surmount rock and rapids.

In its early years, the town grew up as a “break-in-bulk” point on the river. The one-hundred-foot rise from Weldon to Roanoke Rapids (located on I95) prevented large ships from navigating north of the Fall Line. Cargo from ships heading for the interior would be portaged for loading onto small ships to continue the journey.

By the 1820s the Roanoke Canal, a nine-mile network of locks and basins, would allow clear passage from the Blue Ridge to the coast. The canal, fifteen feet deep and forty feet wide with a ten-foot wide towpath next to it, was built by slaves bought and sold by the construction company.

Fifty-foot long boats loaded with produce and hogsheads of tobacco from the upper Roanoke valley would cruise slowly, pulled by mules and guided by boatmen along the towpath.

Roanoke Canal aqueduct high above Chockoyotte Creek with its handsome arch and fine workmanship is a highlight of the Roanoke Canal walking path

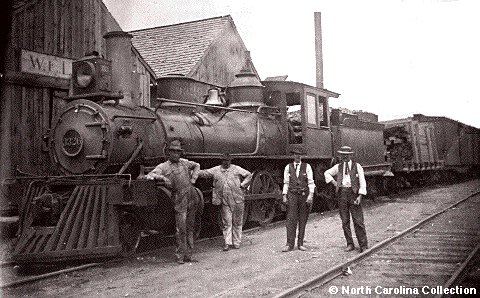

Ten years later, the town became a nexus for railroads to Petersburg, Raleigh, and Wilmington. Weldon’s Apple Orchard was now the center of railroad hustle and bustle. It seemed appropriate to shorten the name of the town to Weldon. In 1840, a line linked Weldon to Wilmington, a distance of 160 miles, and Weldon became home to the longest railroad in the world.

Railroad building at Weldon circa 1840. Today this route is operated by CSX Railroad.

CSX Weldon-to-Wilmington today. Kayakers on the left could be headed to a Roanoke River Partners campsite on the river. Photo credits: Emily Chaplin/Chris Council

The Petersburg-Weldon-Wilmington route became the “lifeline of the Confederacy” during the Civil War. The line moved goods and supplies from Wilmington to Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Transport continued until the Battle of Globe Tavern in 1864 damaged rail lines in Virginia and ended Lee’s railroad connection to North Carolina.

National press took notice of this lively town, with its canal boats, steamboats, highways and rail lines. Weldon could have become a major railroad hub in the southeast.

But its inhabitants strongly objected to this Iron Horse that invaded their lives with noise, and blocked road crossings and frightened animals into bolting. In an unusual rebuff to “progress,” property owners put such exorbitant prices on land needed for expansion that most railroads ceased operations.

During the late 1800s the Roanoke Canal took on a new role. Its waters powered cottonseed, corn, peanut and fabric mills.

Electricity generated by the canal’s clean water power propelled towns into the twentieth century.

Remains of the Roanoke Canal today in Roanoke Rapids. The canal managed a 100 foot drop from here to Weldon. Visit Halifax photo

Today, Weldon is a quiet Piedmont town off Interstate 95 (except during bass tournaments). The old cotton mill is a picturesque destination for tourists and shoppers. In spring, migrating striped bass lure fishermen who compete in bass tournaments.

Slavery and the Roanoke Canal

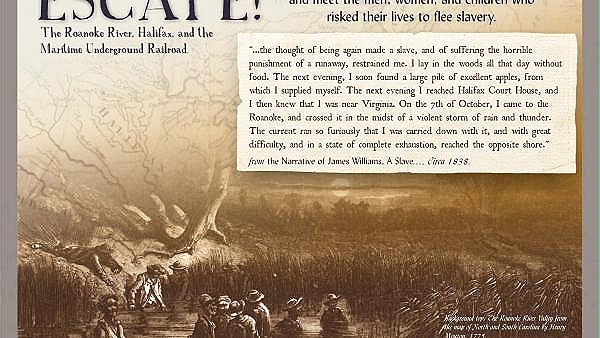

Now let us consider the Roanoke Canal of ante bellum years from yet another perspective: its role in a complex escape route for fugitives along the Maritime Underground Railroad.

The town of Halifax at the northern terminus of the Roanoke Canal and other towns actively assisted fugitives. Dense woodlands and steep banks along the Roanoke River made good hiding places for fugitive slaves but dangerous crossings.

The free black community in Halifax would feed, hide and guide fugitives along the way. In an unexpected twist, the Canal was the escape route for many who did its digging and building.

The Civil War and the Albemarle Ram

The tides of town and countryside would turn with the Civil War. Union gunboats patrolled the Sound and rattled up and down rivers causing destruction to buildings and supplies. Plymouth was heavily damaged and captured in 1862, but relief soon came from an innovative behemoth.

Hidden away in a Halifax cornfield was the Confederate Steam Ship CSS Albemarle, a 152-foot armored ram clad in two layers of two-inch steel plates, apparently invincible. Enemy shells bouncing off her hull were likened to the sound of pebbles in a can.

She’d been designed by a nineteen-year-old engineer and built of scavenged steel in a makeshift shipyard among corn stalks way up the river.

Photo of the Confederate Steamship Albemarle ram, probably at the Norfolk Navy Yard, after its sinking and salvaging at the end of the Civil War before its final scrapping

Water levels were high on the Roanoke as the ram began her maiden voyage, so she coasted easily over chains laid across the river by Union sailors. The CSS Albemarle then steamed south to recapture Plymouth.

During her brief reign on Albemarle Sound she rammed and sank Union ships, terrifying their crews. It looked for a while that she would be the maritime savior of The Confederacy, ramming her way along Albemarle Sound, through Hatteras Inlet on the Outer Banks, into the Atlantic and south to Wilmington seaport.

Such dreams would not become reality. In 1864, a small ship with courageous Union sailors, in particular a Lieutenant Cushing, attached a torpedo to the ram. Its destruction was reported as ” one of the most daring and romantic naval feats of history.” The short life of this “invincible” steamship, the CSS Albemarle and its encounters with Union ships is just as daring and dramatic.

A replica of the steel-hulled CSS Albemarle can be seen today at the Port o’ Call Museum in Plymouth. Go Wild Washington County Photo

Despite serious damage to the city during the war, Plymouth quickly rebuilt and became one of the busiest ports in the state, shipping naval stores and lumber. Nearby Williamston became a port for craft running between the coast and the interior.

Man and the River

From early times, on an April weekend the Roanoke would teem with millions of striped bass, shad, herring and white perch. Fishermen would crowd its banks with all sorts of gear for catching them.

Massive runs of striped bass would begin in April, in stages, females first, followed by males. It’s a frantic race back to natal grounds for spawning, a long distance swim from miles out in the ocean through Outer Banks inlets, 55 miles up Albemarle Sound, then another 100 miles up river to the fall line. Business conducted, they would return to the ocean where they roam far afield. It was a saga of centuries, long before man appeared on the rivers.

Spawning striped bass (rockfish) feeding on spawning herring. Rivers ran solid with churning fish in past centuries. Field and Stream artwork

In 1585 the artist John White chronicled striped bass on the Roanoke that were five or six feet long. They were an important food for Indians and colonists.

Striped bass are the predators of the river. They feed on herring and shad and blue crabs. They never stop growing, and a ten-year-old female can easily weigh 30 to 40 pounds.

At the end of a thirty-year life span a striped bass can weigh up to 100 pounds, with one recorded at 125 pounds in 1891. That is a substantial meal, but since they cannot be salted, they must be kept on ice until eaten or shipped.

Unlimited Fisheries?

After lean winter months for families, the arrival of herring, shad and striped bass was a time of hard work, high spirits and celebration. A good herring catch, salted, was insurance against hunger during winter. There seemed no limit to the ways fish could be corralled. Even youngsters put buckets to river.

Case in Point: On a spring day in 1896, a fishery biologist counted 435 people fishing with bow nets on the river below Palmyra (north of Hamilton). Bow nets were indispensable: versatile and easily manned. Fishermen could dip herring out of weirs, or catch them from shore, or scoop striped bass from the shallows near Weldon.

Bow net cast along the river 1950. A bow net was prized by its owner, usually made from ash and handed down through generations. Courtesy Jack Dudley

Weirs were more or less permanent, made from cedar slats driven strategically into the muddy bottom to intersect a river channel. The structure would guide fish into a pound that confined them until the weir’s tenders arrived to scoop them out with bow nets. During heavy runs it was almost impossible to empty the weirs quickly enough.

A weir near Plymouth circa 1905. From the NOAA Historical Fisheries Photograph Collection. Courtesy, National Archives

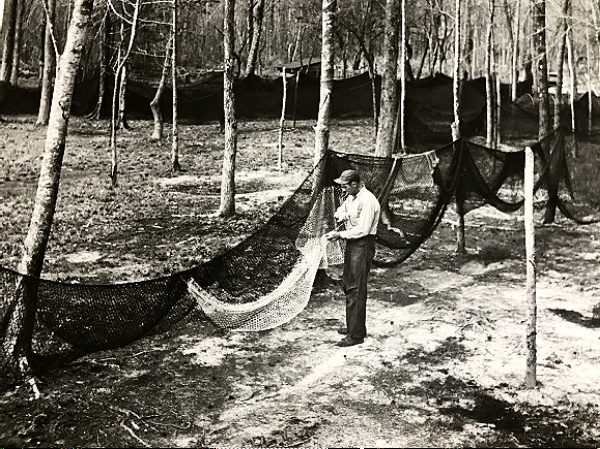

The cypress dugout of Indian tradition was still being used in the nineteenth century on the lower part of the Roanoke. Fishermen logged ancient trees and worked the boles themselves. In the picture below, drift nets are hung up to dry on poles after a morning of fishing.

On a single day in 1896 30 boats and 169 men were observed working eight seines along the Roanoke. Fishermen at Jamesville would set seines half a mile long to catch as many as 20,000 herring at a time. Long drift nets and skim nets resembling large ladles were used, too.

In 1876 one seine was recorded catching 35,000 striped bass weighing 80 or 90 pounds each. For those who wonder how a two- or three-million-pound catch was hauled in, I can only surmise that a capstan on shore powered by mules, men, or steam engine would have slowly turned the cables to reel the net in over several hours, tightening the circle, until an army of tenders in the water could heave the seine onto shore and scoop up the fish with bow nets.

Bringing in the fish, in this instance, shad, a much smaller fish that was prey to the striped bass. Engraving from Harper”s Monthly,1879

Fish camp on the river, drift or seine net probably being set out to dry and be repaired. Note the length as it skirts around the trees. Courtesy Jack Dudley

Near Hamilton and Williamston waters flowed rapidly enough to operate unattended fishing machines, strange-looking contraptions that were actually pound nets with paddles powered by water flow. At times they sank under the weight of colossal catches.

While fishing wheels probably drew curious spectators to the banks of the Roanoke, seine fishermen still brought in most of the river’s fish around the end of the 19th century.

Back in the high fishing days from March to May of the 1800s — and later — slaves and free blacks did most of the fishing on the Roanoke and other rivers in the Albemarle. They were sailors, river boatmen, pilots, and ferrymen, too.

Fishermen guide a flat boat with barrels of salted herring down the Roanoke ca. 1875-1900. From NOAA Historic Fisheries Photograph Collection. Courtesy, National Archives

Watermen would put up salt herring to last through the winter, maybe hire out to a big company or sell a few barrels for much needed cash. When the fish stopped running in May they would go back to farming, hunting and trapping, or maybe working “in the logwoods,” as people used to say.

There was high demand for shad and herring up and down the Eastern Seaboard. When the Great Dismal Swamp Canal opened, ships could steam down from the Roanoke through Albemarle Sound and up the Pasquotank River into the Canal, then to Norfolk, Virginia.

This photo of a steamer on the Tar River, 1900, probably carrying cotton or cottonseed, is similar to those running on Albemarle rivers with cargoes of fish. Steamers can maneuver shallow rivers because they do not have the deep keel of sailboats. Edgecombe County Library collection

Nostalgia for those heady spring days of celebrating mighty catches that would sustain families through the winter remains strong today. Until recently the Cypress Grill, steps away from the river in Jamesville, was a destination of choice for locals and out-of-towners who wanted their herring fried crisp, light or dark, bones and all — the only way to eat herring.

The building was simple cypress board and batten, dating from 1948, open only when the fish were running. You could get herring with fixins’ and scrumptious chocolate pie for a real bargain.

But traditions die. A fire took the building in 2018 and the herring served did not necessarily come from the Roanoke any more. There are few spring celebrations now. A way of life has become a footnote in a history book.

What happened to the Fish?

Nobody except a few visionaries thought the fish would disappear. Their migrations were taken for granted, a centuries-long saga of springtime exuberance. Albemarle rivers were once the premiere spawning grounds for herring, shad and striped bass, but especially the Roanoke for striped bass.

Yet by 1988 striped bass numbers were dangerously low, below 200,000 in a season, a day’s catch in past centuries. Two decades later shad and herring would be labeled depleted fisheries.

Before we go further we must remind ourselves that the Roanoke River is not just a winding blue line on the map. It crosses state lines and it is the sum of all the arteries that roll and twist and finally merge into it. That is the nature of any river basin.

Its character comes from big tributaries (like the Dan River) and from countless creeks and riffles barely noticed except by kids who catch frogs. What happens along the least of these can ripple through the network until the effects finally touch the river.

Schematic of the upper Roanoke River basin showing the network of waterways that feed the river, from its western beginnings in the Blue Ridge to Lake Gaston in the east. Brown line is VA/NC boundary. Note that most of the upper Roanoke’s basin lies in Virginia. US Geological Survey

Here is why the fish stopped coming.

We were greedy

Colossal catches with improved gear in the 1800s began to cut into fisheries, worrying prescient observers, though most warnings were ignored. When motors replaced sails, fishing became even more efficient. In the 1950s and 1960s, large trawlers waited out in the ocean to scoop up fish coming and going through Hatteras Inlet. All ages, all sizes were fair catch. Gradually, schools consisted of smaller and smaller, younger and younger fish.

Without enough fish that can reproduce, particularly those hefty, thirty-pound, ten-year-old mamas who can annually lay a million eggs for every ten pounds of weight, courted by cohorts of upstart males who nudge and push (nature’s way of preserving genetic diversity), a fishery dies.

By mid-twentieth century sports fishermen were competing with commercial fishermen for smaller and smaller catches of smaller and smaller fish, with strict limits on size and catch. The situation was about to get worse before it got better.

We messed up habitat

Construction, farming and forestry silt in acres of bottomlands. Ditching and draining fields, straightening channels, and clearcutting forests and riverbanks muck up a river with sediment that smothers larvae and clogs gills of young fish.

Clear-cutting was the most common forestry practice from European settlement onward. Huge swaths of land can remain barren with negligible regrowth of original woodland species, and is often converted to municipal, industrial, or agricultural uses. Foragable Community photo Jan 2020

Today, Best Management Practices for forestry and farming and woodland buffers along river banks can protect rivers from damage, but protective measures must be applied consistently and conscientiously.

We Poisoned Waters

For decades, dilution was the solution to pollution, and rivers were the target for washing away pollutants. Internet photo

Industrial sewage carries chemicals like dioxin, mercury, PCBs. Municipal sewage carries bacteria and heavy metals.Urban runoff carries oil and gas.

Farm runoff carries fertilizer and pesticides applied season after season, year after year, with no release from the treadmill.

Bit by bit waters become contaminated.

This state-of-the-art wastewater treatment plant in Roanoke VA recycles sewage sludge into fertilizer for farms and tree plantations. The catch is: wastewater may be cleaned up but heavy metals and other elements can concentrate in the remaining biosolids. Neighbors of farms object to odor and insects. Roanoke.com photo

Contaminants stress fish and make them susceptible to disease and parasites.

Or, fish die in great numbers when dissolved oxygen plummets.

Or there are accidents.

Fish kill in Tinker Creek occurred when a hole developed in a steel drum and toxics leaked over a period of several hours

Two Particular Poisons

Two chemicals of concern illustrate how difficult it is to clean up soil and water once poisoned.

One is PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls). The other is dioxin. Both are highly toxic and long lasting. They sink into bottom sediments where they remain, and they bioaccumulate in fish tissue.

PCBs came from a manufacturing plant in Virginia, Tetra Tech, Inc. In 1979 federal law made it illegal to manufacture, distribute or use PCBs, but they are still produced in small quantities as by-products of some manufacturing processes.

Dioxin entered the lower Roanoke at Plymouth when Weyerhaueser began pulp and paper production in 1937. Chlorine is used to bleach pulp. The process contaminated groundwater, sediments, surface soil and water, and fish tissues with dioxin and heavy metals including one of the most toxic, mercury. Though the plant is closed today, the damage remains.

Weyerhaeuser Company pulp and paper mill on the Roanoke River in Plymouth was one of the largest pulp and paper producing plants in the world before it closed. Photo by P. Nurnberg

Remedial action is ongoing in both situations. It has been ongoing for almost half a century, since the 1980s. It involves a tap dance of mandated studies and plans and proposals and reports that uses sleight-of-hand to gloss problems with opaque veneer.

Fish consumption advisories for dioxin in catfish and carp exist in Albemarle Sound. (Statewide for mercury.) Fish consumption advisories for PCBs and mercury exist for carp, catfish and striped bass in tributaries to the Upper Roanoke.

These advisories effectively limit inexpensive and healthy additions to the diets of subsistence fishermen. Official statements hasten to assure people that advisories are not prohibitions but information to help people make educated choices.

One big win for the basin: Virginia Uranium’s 2007 proposal to mine dirty, low-grade uranium ore was nixed in 2019 by the US Supreme Court who upheld the state’s ban on uranium mining.

We Changed the Flow of the River

Changes made to river flow were a coup de grace for striped bass.

In August 1940 heavy summer rains and a hurricane drove the Roanoke to 31 feet above flood level. Towns were inundated. Thousands were left homeless. Crops were ruined. Businesses were destroyed.

Although loss of life was minimal. this reminder that the Roanoke could be a River of Death was an alarm call for action.

Citizens clamored for protection from floods. Within 15 years Kerr Dam, the largest in the river’s basin, and a string of seven other dams were created to produce hydroelectric power and control flooding. Impoundments formed by dams became popular destinations for anglers seeking striped bass raised in fish hatcheries for stocking in lakes. These striped bass do not migrate.

Aerial view of Kerr Dam and its lake that straddles the Virginia/North Carolina border, a popular destination for outdoor recreation since the 1950s

The Fish Paid The Price

Arbitrary releases from dams disrupted natural water flows. Growth of hardwoods declined. Turkey nesting declined. And by 1988 the striped bass fishery, numbering fewer than 200,000, was on the verge of collapse.

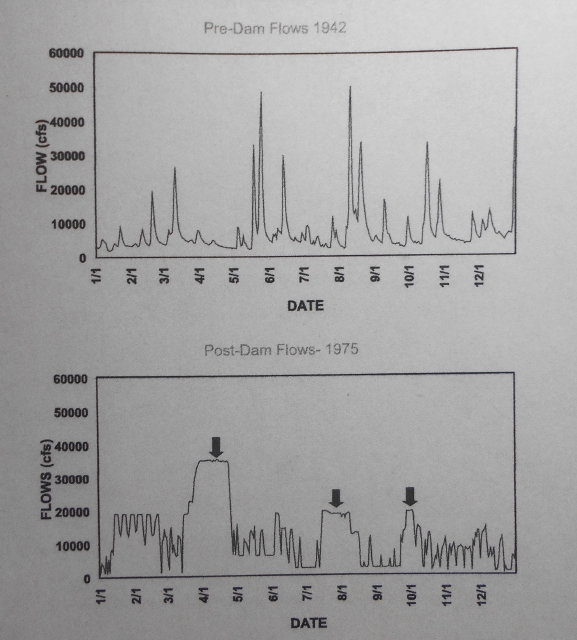

The flow charts below show how arbitrary releases differed from natural flow.

Comparison of pre-dam, or natural flows, and post-dam flows. Arrows show prolonged flooding, detrimental during spring when wildlife is reproducing and fish are spawning. US Fish and Wildlife Comprehensive Plan for Roanoke River, 2005

Something had to be done. The striped bass fishery was an economic powerhouse for North Carolina, yet the problems lay with Kerr dam in Virginia that protects North Carolina towns from floodwaters.

The solution seemed to lie in releasing water from reservoirs in ways that more closely mimicked natural river flows. A new release regime apparently worked. Health of bottomland hardwoods and wildlife reproduction improved. There were fewer crashes of dissolved oxygen that causes fish kills.

And striped bass spawning was successful. By the year 2000 striped bass population numbered two million fish, a mere snack compared to rollicking catches in the old days, but a gratifying turn of numbers.

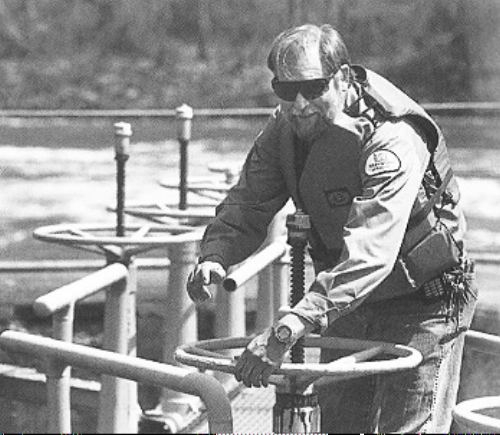

Schools of fish often do not use fish ladders on dams. Here, gates were installed and are being opened to allow a school of shad to get to spawning grounds upstream. US Fish and Wildlife Service photo

Fisheries experts are a dedicated lot. They’ll do whatever they can to help fish thrive. A robust tagging program monitors growth rates and migration (some tags have come in from beyond New England).

Healthy females are recruited from the river to supply eggs for stocking programs. Restrictions on catch aim to keep fish populations high. Barbless lures protect fish during catch-and-release programs.

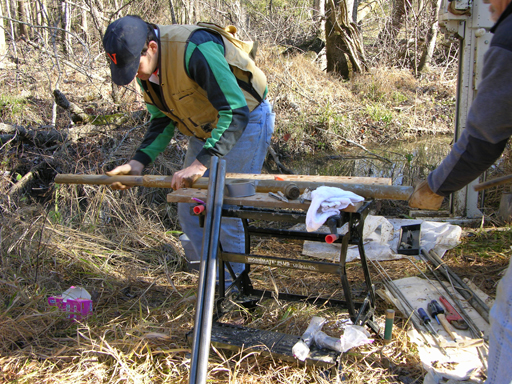

Field research continues on the Roanoke. The. US Fish and Wildlife maintains research activities in critical areas of the Roanoke River National Wildlife Refuge US Fish and Wildlife Service photo

Yet fish population is so low that North Carolina’s Dept. of Environmental Quality has tightened restrictions. Recreational fishermen were restricted to one fish per person per day during the 2021 spring season.

When fisheries are so weak weather can be a villain. Flooding and high river flow can interfere with spawning. Eggs and fry floating down river toward their food supply in Albemarle Sound are tossed onto banks or marooned off course in wetlands or sluggish streams.

Loss of fry over a number of years reduces spawning in future years. In 2021, Total Allowable Landings were limited to 51,000 pounds split evenly between commercial and recreational fishermen.

Still, restrictions don’t deter recreational fishermen from angling for the feisty striped bass in this river that is the rockfish capital of the world. They are conscientious (as are commercial fishermen) about following regulations because they want this fish that has fought to survive centuries to live on.

Sustainable River Progress is working toward more natural flows along the Roanoke. See VisitHalifax.com

A National Wildlife Refuge is Born

We have come a long way in our attitudes about land and water. We’ve learned that wetlands are not wastelands, that there must be a balance between economic gain and environmental health.

Follow-through can be half-hearted, but in 1989 a giant step was taken on the Roanoke toward meeting these resolves. The 33,000-acre Roanoke River National Wildlife Refuge was born out of almost ten years of resolute cooperation between private and public agencies.

Kayaking at Devils Gut in the Roanoke River Wildlife Refuge among cypress and tupelo trees. Photo by Carl Galie

The Nature Conservancy, US Fish and Wildlife Service, NC Wildlife Commission, and the State of North Carolina executed a complex strategy of donation, bargain sale, and land swap. Additional land managed by these agencies outside the refuge totals over 100,000 acres.

The Inner Banks

Counties and towns in the Roanoke basin are developing imaginative destinations for eco-tourists who would tread lightly on the land.

These Inner Banks counties, as they are now called, are no longer simply pass-throughs to sandy beaches and ocean waves on a sun-glittered coast.

Albemarle counties are parlaying their down-home hospitality and the quiet beauty of their environment into a destination for eco-tourism that does not depend on fern bars and boutiques.

They are building an economic infrastructure that will support a brand of tourism that highlights the history and resources of their land.

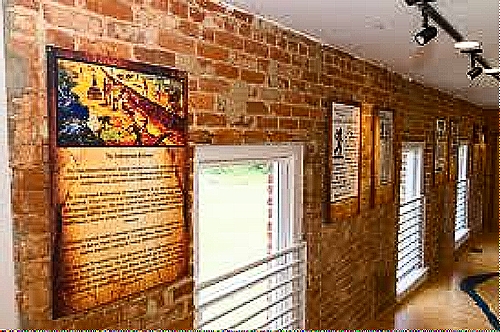

Visitor centers, small museums, restored plantations and river boardwalks speak of history. Along the Roanoke, the Port o Call Museum in Plymouth, the Charles Kuralt Trail near Williamston, The Roanoke Cashie River Center and Hope Plantation in Windsor, and the Maritime Underground Railroad museum and trail in Halifax are some examples.

Port o’ Plymouth museum on the Roanoke River explores the history of the area and the Civil War. Here is a replica of the CSS Albemarle Ram

And in most towns you can find an old-time general store where you can pick up an ice cream cone as you stroll a historic Main Street.

Hiking, kayaking, hunting, fishing, photography, birdwatching take visitors outdoors. The Roanoke River Paddle Trail, initiated by Roanoke River Partners, is a string of sixteen platforms for tent camping in refuge bottomlands.

The ultimate goal of Inner Banks counties is to introduce visitors to the natural wonders and rich history of a region that has been intimately linked to the history of our country.

Rising Seas and the Town of Windsor

The town of Windsor in Bertie County is sandwiched in a vice grip of waters.

Let us use this town as an example of the ways rising seas have affected a community in eastern North Carolina. For orientation, take a minute to find the Roanoke and the Cashie Rivers on the schematic below. (Cashie River is pronounced Ca-shy.

Schematic showing the Cashie and Roanoke Rivers flowing through the delta before reaching Albemarle Sound. roanriverdeltasound-bioone.jpg

Windsor lies downstream on the Cashie River, where Route 17 crosses the river as it begins to widen. Above the town, the narrow river runs fast and turbulent for about thirty miles, descending from an ancient geologic terrace before it reaches sea level at Windsor. There, on flat bottomlands it loiters and fans out on a leisurely voyage to Albemarle Sound 25 miles away.

Meandering marshes and gamelands along the Roanoke and Cashie Rivers as they flow toward Albemarle Sound

Before we discuss how this set of geologic features can turn so deadly, let’s spend a moment exploring Windsor’s past. It’s a hospitable town with engaging people and a history that reads like folklore.

The town emerged as a thriving commercial center in the 1700s, its wharves crowded with tar, pitch, turpentine, staves, salt pork, salt fish and tobacco — raw materials from the south bound for the north for shipbuilding and consumption.

The W&P railroad was a local narrow-gauge railroad that ran goods and passengers from Windsor north to the small town of Ahoskie. Named for its founders, it was so unreliable most people called it the Walk and Push because that was what riders often had to do.

By the 1720’s Tomlinson’s Ferry operated a few miles down river, a five-minute crossing guided by cable, no steering, no brakes. It’s still operating today, a convenience for locals, a curiosity for tourists. It’s powered by a John Deere diesel engine but still no steering, no brakes.

The name is changed, though. In the early 1800s the post office near the dock needed a name. So the story goes, the postmaster said he didn’t care what the post office was called. Some wit who apparently knew a little French, suggested Sans Souci (literally, Without Care) and it stuck. So much more elegant than I Don’t Care, don’t you think?

Especially if you need a name for the moonshine you are marketing. During Prohibition, Sans Souci was the site of a large still on the north bank of the Cashie River. This was quintessential entreprenurial enterprise, operating round the clock with three shifts a day and a steam whistle to announce shift changes. The moonshine was smuggled north to New York City where Sans Souci Whiskey was much in demand.

Today, visitors can take a short walk on the Cashie Wetlands boardwalk, spend some time at Livemon Park and Mini-Zoo, tour historic Hope Plantation, learn about wildlife at the Roanoke Cashie Visitor Center, and visit the Craftsman and Farmer’s Museun, with a stop at Bunn’s Bar-B-Q. If you choose to camp, you can spend the night at one of the town’s treehouses.

The Town of Windsor rents elevated treehouses with boardwalks for campers and offers river tours and kayak rentals.

While the town has much to offer, it has been in the crosshairs of major storms, hurricanes, and especially floods. Its location on the flat coastal plain means that, during storms, swollen cataracts from the upper Cashie crash down onto Windsor at the same time storm surges from Albemarle Sound push up the river into town. Clashing waters churn and the town is inundated.

From 1999 to 2016 the town was walloped by four major floods caused by hurricanes and tropical storms. Hurricane Floyd, one of the most damaging to hit North Carolina, caused 20-foot floods. Some residents woke up the morning following the storm to find water lapping at their bedsides.

Past environmental decisions and rising water levels contribute to calamities.

Because of changes to flow, water reaches Windsor even more quickly today than it used to. In the 19th century millponds offered some flood control. Roots of hardwood trees absorbed water. New culverts and bridges, on the other hand, speed flow. As more frequent and more intense rainfalls saturate the ground, drainage becomes more critical.

This culvert is an example of how natural flow quickens and prevents absorption of excess water into the surroundings

A Changing Environment

Water levels in Albemarle Sound are rising — several inches in the past half century. This means rivers don’t drain as quickly, more chance for water to pile up during storms.

Residents, hard-wired to the land, are exploring a variety of ways to cope with new threats: relocating structures, or raising them, even building dikes. Good ideas, perhaps, but costly.

In comparison, natural environments are resilient during change. As water levels rise, bald cypress and tupelo will replace upland forests whose seeds will seek dryer ground to germinate. Grasses will replace cypress and tupelo and fresh water marshes will expand. As plants shift, some animals will move out while others will take their places.

Rising water temperatures can affect fisheries. For instance, striped bass need water temperatures in the sixties to complete spawning, herring prefer cooler waters. Changes in climate can affect the timing of their migration.

The earth’s climate has been changing throughout millenia. Sea levels rise and fall depending on prevailing climate. Sea level today has been rising for centuries since glaciers melted. Plants and animals have adjusted gradually as they moved around to seek hospitable conditions. As climate changes, ecosystems will adjust. But people with roots must think about how they are going to manage.

(The issue of climate change is discussed in more detail in the last chapters of Voyage Through Centuries.)

In the meantime, though we must plan for future generations, let us continue to appreciate this land. Let us spend more time enjoying its gifts. And let us seek to preserve what is fine about it.