Carolina moon keep shining, shining on the one who waits for me. . .

Anyone who has seen a harvest moon rising over the Perquimans River, bald cypress silhouetted in milky-gold light, will vouch for local lore about this popular song crooned in the mid-fifties.

Inspiration came to the composer, so the story goes, as he crossed the Town of Hertford’s “S” bridge on a bright moonlit night, anxious to be reunited with his sweetheart in Florida.

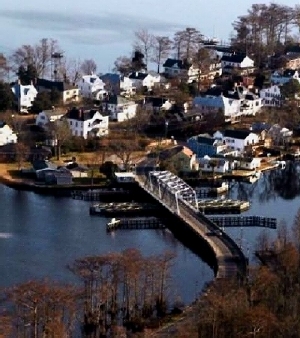

For almost a century, this swing-span “S” bridge was a Perquimans County landmark, the last bridge of its type in North Carolina.

Of Wildlife, Winds and Tides

The Perquimans is not a mighty river, but its shores were probably the first to see permanent settlement in North Carolina by Europeans.

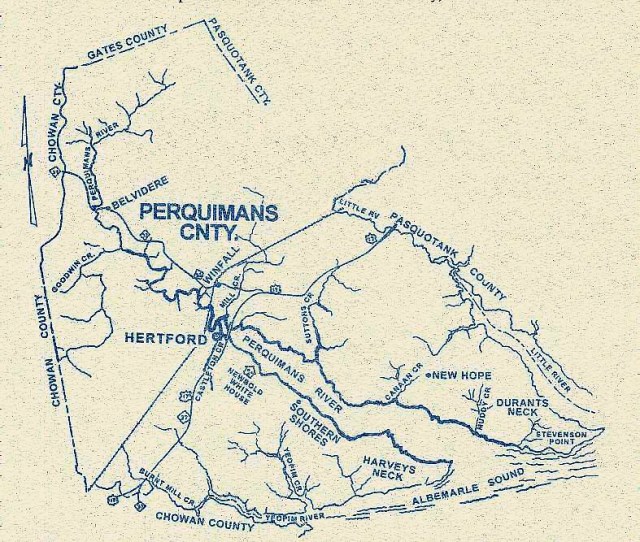

The river strikes through the heart of its county, a county encompassed by water: the Yeopim River to the west, Little River to the east, Albemarle Sound to the south, and the Dismal Swamp to the north.

The watery environment will shape the history of settlement on land.

Perquimans County showing the Perquimans River as it flows south, bounded by the Little River on the east and the Chowan County and the Yeopim River to the west. Artwork by Elaine Roth

Rising in what was once the Great Dismal Swamp, the Perquimans River meanders about 30 miles until it meets Albemarle Sound.

This 1770 map shows the Perquimans and its sister rivers that flow from Virginia into Albemarle Sound

The river’s upper reaches are narrow, deep and winding.

So winding, the Town of Hertford, county seat and commercial center, sits on a peninsula, and views of water seem to be everywhere. South of town the river straightens, widens, and flows some twelve miles until it reaches the Sound.

The Town of Hertford showing the curve of the swing bridge across the river. Our State Magazine photo

So winding, this 30-mile-long river has 100 miles of shoreline, with coves for leisurely kayaking or lazy fishing.

A myriad of tea-colored creeks feed the river, their slow-moving waters stained by tannins leached from decayed life in spongy swamps. Shaded by red maple, bald cypress and black gum, the creeks are refuges for wildlife.

Perch, flounder, catfish, large-mouth bass and sunfish, permanent residents, make for good fishing. Herring and striped bass are spring migrants.

The upper reaches of the river and its creeks are wild and unspoiled, for an afternoon of quiet canoeing. aheronsgarden photo

Sweep of wind, not lunar tides, governs the depth of the Perquimans River. When winds blow from the north, the river will glide, or hurry, south into Albemarle Sound.

Conversely, when winds blow from the south, Albemarle Sound waters will push upriver, raising the depth. bottling up around the narrows at Hertford if the push is strong.

It’s not just water level that changes. Salinity changes, too. Upper swamps flow with fresh water; the water in Albemarle Sound is brackish. As Sound water sweeps in, the river’s salinity increases. Blue crabs, for instance, like brackish water and take up residence, sometimes as far north as the town of Hertford.

Blue crab in underwater meadow of fresh water grasses. Salinity, water temperature, seasons and rainfall can influence the migrating behavior of the crabs

There is a robust blue crab fishery in these waters, and native blue crabs are available locally, as long as care is taken to avoid over-fishing.

Who Owns the Land?

George Durant had done his homework. Along with hunters and traders, he came to this Country with the first seaters . . . bestowed much Labour and Cost in finding out the said Country . . .and then made his choice and sealed it with a deed.

Freely translated, the Indian word for this country, Perquimans, means Land of Beautiful Women. There are no records to support or confound the claim, possibly because the English were more interested in pushing this small, loosely organized Algonquin tribe off the land than in recording the charms of Indian maidens.

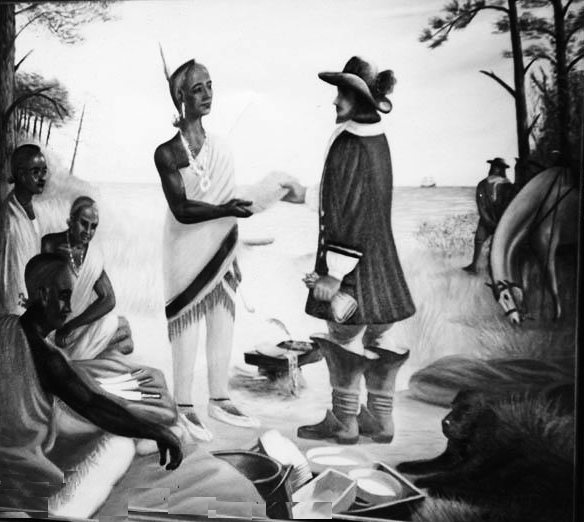

Either way, enterprising settlers were hungry for land and fortune. The first recorded real estate transaction in North Carolina was the sale of land in 1661 now known as Durants Neck:

Know all men by these presents, That I Kilcocanen, King of the Yeopim, have for a valuable consideration of satisfaction received with ye consent of my people, sold and made over, and delivered to George Durant, a parcel of land lying and being on Roanoke Sound (Albemarle Sound) and on a river called by ye name of Perquimans. . .

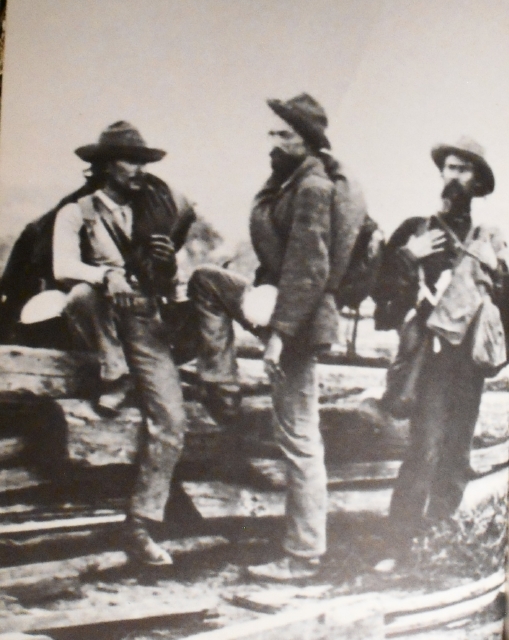

Artist’s imaginative view of treaty between George Durant and Kilcocanen, King of the Yeopim. There is no record of what “valuable consideration” was received

In this age of exhaustive title searches, the free and easy transfer of land that belonged to no one in particular is hard to reconcile.

How the King of the Yeopim acquired this and other parcels he apparently sold off is not known. Not that it mattered. A friendly sale sealed with ink, and not muskets, betokened future civil relations, temporarily, until the tribe was eventually dispossessed.

Only two years later King Charles II would deed this same land and a vast swath of land in the Carolinas stretching to the Pacific Ocean (also land in New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania) to allies who had supported him in his clandestine efforts to attain the throne.

Lords Proprietors they were called. They were chartered with bringing order to this wild new territory, but, more realistically, they were anticipating easy money.

After decades of dissension and rebellion, King Charles would buy this land back from the Lords Proprietors, who had not made their fortunes and were happy to be rid of the thankless burden of keeping order in an untamed wilderness.

Colonists were supposed to be vassals in a feudal society, but the nature of the territory and the settlers forced proprietors to yield power and privilege to them. Now the king wanted colonists to be answerable to parliament, lest they become too independent.

Unwittingly, the King’s gift to his friends created headaches in the colony. Disputes and litigation were rife. Settlers who had established their homesteads, some decades before, resented newcomers who came with royal land grants that had inaccurate boundaries.

Colonists were not quick to give ground. Contentious soreheads in the eyes of English profit-seekers, no doubt. Appointed magistrates had the task of keeping order.

A will dated February, 1660 illustrates the extent of settlement. James Took formally bequeathed furniture, silver, pewter, also by default a featherbed, chamberpot and livestock, to his daughter Dorothy and her husband, John Harvey. Presumably, this and other estates had been established many years before land grants.

Note: The John Harvey dynasty would figure large in Perquimans history (as would the name of Durant). Through the centuries the Harvey lineage would assume leadership in local, revolutionary, and state governments.

The peninsula in south county on the west side of the river is known as Harvey’s Neck, or Harvey’s Point. Today, its southernmost tip is a military training base off limits to anyone non-credentialed.

Land on the east side of the river is known as Durants Neck and figured prominently in early history. (See map.)

Getting Around: Boats and Bridges, Ferries and Roads

Meanwhile, early colonists were mired in more swamp than dry land and isolated from their nearest neighbors in Virginia by the Great Dismal Swamp. Storms added to the treachery of travel — and keeping alive.

Quaker missionary William Edmundson was sorely foiled in swamps and rivers, (even his guide lost his way), and the founder of Quakerism, George Fox, wrote that he had travelled hard through the Woods and over many Bogs and Swamps. . . overwearied by his trek to reach his flock.

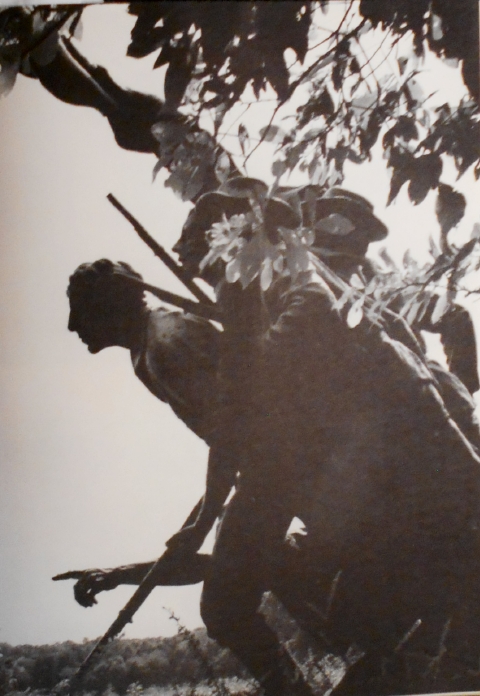

Swamps like this had to be traversed, though trees then were mightier than this second and third growth timber. APNEP photo

In fact, most settlers preferred to travel the Chowan River south from Virginia. Some ended their journey along the banks of the Chowan; others continued south to the Sound and then up the Perquimans River to find land.

Roads were mostly trampled muck and mud, but by the early 1700s magistrates were working on a system of roads that were, unfortunately, never truly satisfactory. Most colonials rode horses, except for the poorest folk who walked.

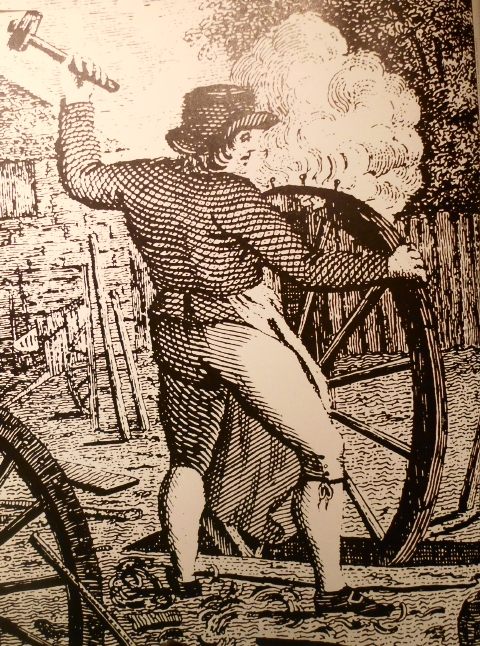

Sturdy, two-wheeled carts pulled by oxen or horses could carry as much as a thousand pounds. The Perquimans Cart, as it was affectionately called, transported farm produce to markets and farm families to church and social gatherings. Fancy pleasure carriages were a badge of prosperity.

Carts need wheels, so a skilled wheelwright was an indispensable member of the community. In early colonial days, wheels were shipped from England.

But the river was the mighty thoroughfare, bustling with an assortment of canoes, rowboats and sloops with shallow draft that carried people and cargo. Everyone seemed to know how to build a boat, though some had more skill than others.

Pick-up truck of the South it’s called. The periauger was one of the most versatile — and rudimentary but clever– colonial crafts. Shallow-draft, stable, ample for passengers or produce, with two masts for sailing and oars for rowing, it evolved from a hollowed-out log cut in half lengthwise with a plank inserted between the two halves.

Eventually, ferry service, licensed by the court, linked communities. The court set fees and hours of operation, and paid ferrymen out of levied taxes. By 1754 ferries were free to passengers during public times: county court sessions, elections and musters.

But ferry-goers repeatedly complained of great delays and danger from high seas during southeast winds that would pile up the water and render it utterly impractible or at Least highly imprudent to cross in an open boat.

The first bridge across the Perquimans River floated on empty whiskey barrels. (A cooperative affair, emptying the barrels?) Twenty-feet wide, it was built in 1798 as a privately owned drawbridge with tolls. Eventually it was purchased by the county for $5786 and tolls for residents were abolished.

First bridge out of Hertford across the Perquimans River. In 1798, tolls were 1 shilling 6 pence for man and horse, 6 pence for a foot passenger, 1 pence each for hogs and sheep, and considerably more for carts and carriages. Photo of postcard

Union forces destroyed it during the war, but it was replaced in 1868 by a second float bridge, this one with a walkway. Repairs and maintenance were a constant drain on the county treasury.

Wrote an editor of a Hertford newspaper: We can justly claim the only float bridge in the world and we can also remark that we are the only people in the world that want one.

High waters dislodged the bridge in 1897 and a new bridge was welcomed with a 207-foot trestle, a 153-foot draw and strict limitations. Crowds were forbidden, and no one was permitted to drive faster than a walk. The former float bridge sold at public auction for $16.

Finally, in 1928 the beloved “S” bridge of concrete, steel, and Carolina Moon fame was put into place.

It was along this stretch of road, almost level with the river, that every passerby would look for — and be sure to find — turtles basking on an old cypress log. Is there any other county in the country that can claim such a faithful group of mascots in its environs?

Not quite a century later the historic swing bridge was replaced, along with its approach to town that had needed regular applications of asphalt to keep it from sinking into muck. There are plans to conserve the old bridge as a historic artifact.

Bridges and ferries were fine for getting around the county but they did not relieve the county’s isolation. Imagine the excitement when the first steamboat rolled up the river toward Hertford in mid-19th century.

Two canals had opened the world to Albemarle folks: the Great Dismal and the Albemarle & Chesapeake. After the Civil War a regular freight line between Hertford and Norfolk dispatched circuses, passengers, produce and lumber on biweekly trips between Norfolk and Hertford.

To assure unrestricted passage, the county ordered road overseers to keep streams clear, and state law prohibited felling trees into the river.

In 1902, 36,000 tons of cargo — lumber, cotton, peas, fish, poultry, eggs, shingles, peanuts, potatoes, guano, and general merchandise rolled down the Perquimans River loaded on steamers bound for Norfolk.

By this time the Norfolk and Southern Railroad was operating between Edenton and Norfolk, with five stops in Perquimans County. Hertford was within two hours of Norfolk and steamer connections to northern cities.

At last the county was linked to other Albemarle Counties and states north — and its residents had daily mail service.

Despite accidents, cattle on the tracks and fires, new markets brought prosperity, in particular truck farming and lumbering. This was also a time when great swathes of the county’s forests were cut down, more than half its acreage.

Today, a network of state and federal highways link Perquimans County and its river to the rest of the world. Happily, there are no traffic jams, the roads are excellent, and the county retains its bucolic atmosphere.

Our State photo of the swing bridge in the foreground and the 20th century four-lane Rte 17 in the background

Steering a Growing County

Creating order out of a trickle of refugees almost four hundred years ago, for that is what we would consider them today, who came to escape persecution, maybe, or hoped for a better life, or just wanted to be in sole charge of their souls, was no easy task.

The ragged oyster seller in London is an example of an individual who would indenture himself as a servant to get a new start in the colonies. American Heritage History

These were resilient, adventurous and, yes, often desperate folk, many with few possessions except their wits. They landed in Virginia after a rough transatlantic sail and had to make their way south somehow, on foot, aboard skiffs, with or without guides, through impenetrable forests, before they found a place in a baffling new land where they could take root.

Here is what they had to overcome as they settled in:

- Isolation.

- Poverty.

- Antagonistic treatment by Virginians.

- Indian unrest.

- Bad water.

- Neglect by the Lords Proprietors.

- Burdensome British taxes.

- An uncertain government.

- And an unforgiving but bountiful wilderness (if you could manage the other hardships).

The following 1709 quote from an itinerant Anglican minister, almost assuredly biased by the comparatively fine, and easy, life he led in England, illustrates some of the hardships.

The people, he says, were destitute of good water, most of that being brackish and muddy, they feed generally upon salt pork, and sometimes upon beef, and their bread of Indian corn. Lacking grist mills, they were forced to beat their own grain, with little difference between the corn in the horse’s manger and the bread on their table. On the whole, the area was overrun with sloth and poverty.

By 1680 the provincial assembly for the territory had established Precinct Courts that heard minor civil and criminal cases and administered operations in each of the Albemarle precincts (another name for counties).

The magistrates, about five or six, the numbers vary, were responsible for probating wills, registering deeds and cattle marks, opening roads, building bridges, establishing ferries, caring for orphans, maintaining public buildings, setting fees for services, such as milling (one-eighth of the corn ground), monitoring ditching and draining, and keeping track of county finances.

Few projects, it seemed, went smoothly. Ditches and canals would often involve construction on a neighbor’s property, so magistrates would appoint a drain jury. The jury would need to visit the site, map the route, negotiate fees for taking of property, settle disputes, and follow up on construction.

Roads and ditches could take two or three years to complete, bridges even longer, since their specifications were more complex and contractors would need to be held accountable to the magistrates for the work.

A site chosen for farm and home could be on high land but surrounding swamps could be dreary and impassable and make it difficult to get produce to market. American Heritage History

Not until 1741 was the first grist mill/saw mill operational in the county. John Pratt had asked permission to begin the project on the Yeopim River four years earlier, but Sickness and many Disappointments, and having to reroute the road to the milldam, delayed completion.

Within the century, there would be nine mills in the county. Sawn lumber, staves and shingles became a profitable export to New England, and people had properly milled corn. Invariably there were complaints about damage to nearby property and roads that the courts would have to resolve.

Sawmill on the river near Winfall, probably erected very late 19th century. Photo from Historic Architecture of Perquiman County

In the meantime, the county was steadily growing, from 50 families in 1670 to about 5,400 settlers a century later.

But in those early days, settlers resented unfair English trade laws. Dissension was apparently so open that the proprietary government called for surrender of all firearms (though how many colonists actually complied is open to speculation).

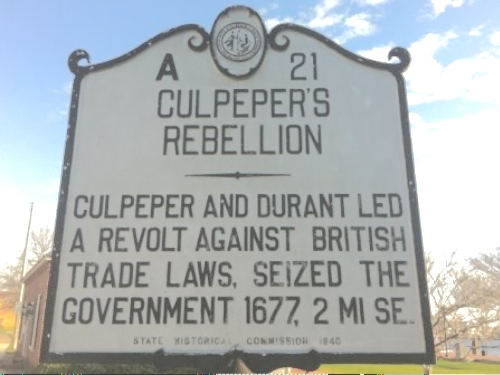

The boiling point occurred with Culpeper’s Rebellion, a confusing scenario at best that actually took place in Pasquotank County in 1677, but Perquimans citizens were involved.

The acting governor (who relied on a cadre of bodyguards to protect him at all times) sparked a minor revolt when he arrested outspoken dissenters. Among them was George Durant of Indian treaty repute who was threatened with hanging for loudly objecting to shoddy governance and unfair taxation (even then).

Culpeper, a bit of a roustabout, and cohorts forcibly set the prisoners free and retaliated by arresting the acting governor. He then seized control of the government and ruled, apparently quite satisfactorily, until he was finally called to trial in England.

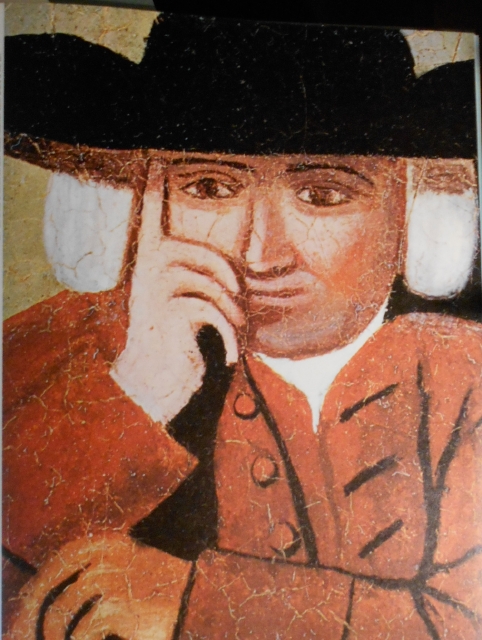

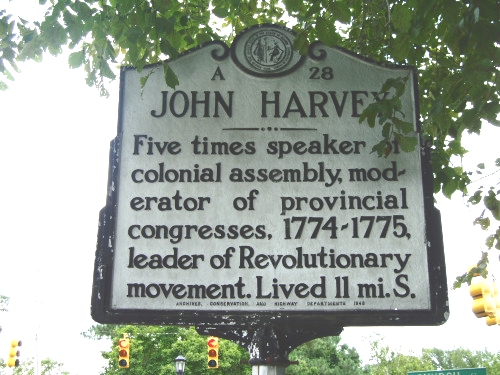

Culpeper expected the worst. Instead, the Proprietors decided to downplay the affair. Publicity about mismanagement and strife in land they were anxious to colonize would not win enthusiastic settlers. Culpeper returned a hero. In the interim, John Harvey, as president of the colonial council, became acting governor of the colony.

Historic North Carolina road sign, Water Street, Elizabeth City . Even then, colonists objected to unfair trade laws

From this time until 1716 the County served as the state’s first capital. Perquimans precinct was a natural choice. It was centrally located and it had a core of well respected and active citizens.

Above all, it had the first public buildings in the colony: a prison that doubled as a storehouse, and a pillory, both built on George Durant’s property.

No courthouse yet. Legislative and court sessions took place in private homes or taverns, and, if the number of taverns licensed in the small town of Hertford (for example, 21 in three years around mid-century) and the dickering over unpaid tabs are any indication, the meetings could be pretty lively events.

The Eagle Tavern in Hertford is an example of the modest prosperity of the times. George Washington is said to have slept here

The first courthouse, a substantial, two-story frame structure did not appear until the 1730s. Less than a century later, a fine large Brick Court House the Majestic appearance of which. . .will add a considerable degree of Splendor to Hertford was ready to replace the old building, up for sale. The courthouse still stands.

Maintaining the courthouse and other public buildings were a constant drain on the county treasury, so magistrates allowed workers to graze their livestock on the greens.

However, stipulated clearly, they were not to suffer. .. (the livestock) to go in the courthouse.

Throughout the upheavals of the Revolution and the Civil War, county government that was initiated in these early years would continue to fulfill its responsibilities to the community.

Oldest brick house in the state, the Newbold-White House along the Perquimans River, was a temporary seat of government in colonial times

Centuries of Tilling the Land

The first settlers who put their axes to clearing land here had no notion that they were laying the foundations for the county’s rural economy. They were doing their best to survive. They took their first lessons from the Indians.

They learned how mighty trees could be girdled until they fell, and how to plant native crops that would become staples for survival. Livestock would be set to grazing cleared areas until fields were ready to be ditched, drained and plowed.

This was small-scale farming, the average holding being little more than 200 to 300 acres, or even less. But scarcely a field exceeded three acres, as so much ditching was needed before the rich soils could produce. Bridges between ditches always seemed to need repairs.

Yet Perquimans farms were counted among the most productive in the Albemarle and value of acreage after ditching increased handsomely.

Today, the view of a harvested farm field in the fall adds a certain tranquillity to the landscape and is a reminder of changing seasons in Albemarle lands. aheronsgarden photo

Farmers used simple hand tools then: hoes, scythes, shovels, and axes. Scything wheat left stubble in the ground that served as green manure and enriched the soil. Later, more advanced plows pulled by oxen or horses made a cleaner sweep of the fields.

Mild winters and fertile soil fostered lots of experimenting during those early years. Wheat and rice were tried, along with corn, tobacco, potatoes, beans and peas, cotton, flax and indigo.

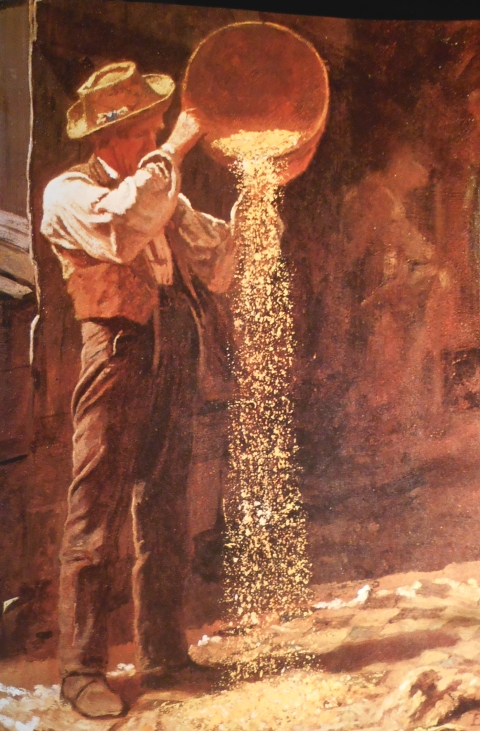

Threshing wheat with hand flails. Exported in the 18th century, wheat is still grown in the Albemarle today. Preparation was obviously labor-intensive. From Butterworth, the Growth of Industrial Art

Wheat was in demand by New England colonies. According to the Reverend Urmstone in 1714, New England ships sweep all our Provisions away. . .There are above 7 now waiting like as many vultures for our wheat & more daily expected. . .

Winnowing wheat, or separating grain from chaff by catching grain on a blanket while breezes blow the chaff away. American Heritage History

Some crops were not worth the effort. Tobacco robbed the soil and grew better in Virginia. Rice languished but flourished further south. Colonial cotton was poor quality compared to cotton from the West Indies, and England was wedded to wool and linen.

Cotton and flax were raised for homespun, or country clothing, from fiber spun on a linen wheel found in most houses. But it was never considered as fine as fabric that could be imported from England.

With country commodities like wheat, produce, and deerskins, a cash-strapped farmer could barter surplus crops for goods from local merchants. As society grew more complex, gold, silver and paper money replaced country commodities.

But it was Indian corn that fed people and livestock and made good liquor and was easy to grow and harvest and ship. It soon became a profitable export.

Even before the Revolution, 65 per cent of corn grown in Perquimans and neighboring Albemarle counties, was slipping through the Outer Banks barrier island via Currituck Inlet (before a hurricane destroyed it in 1828) headed for New England and the mid-Atlantic states.

Livestock, fur and shingles rounded out the exports. Imports included rum, molasses and sugar from the West Indies; clothing and manufactured items came from northern colonies and England.

By mid-18th-century, most homes had gardens and orchards whose excess fruit was skillfully converted to quantities of liquor.

This expertise became a happy advantage when imports of rum were cut off by the British blockade during the Revolution. Small, independent distilleries produced whiskies and brandies, and for a while distilling became one of the leading industries of the state.

The fruits of home orchards did not bring the returns that cattle and hogs did. Wide open, unfenced areas served as a great commons for free-roaming livestock, ownership identified by brands recorded in the county.

Livestock were on their own, with no forage for winter, no shelter, no protection from predators. (Hogs, better suited to free range, fared better than cattle.) A traveler in 1783 noted that most of the farmers, although they keep a number of cattle in the woods, can hardly winter one milch cow at the house and therefore go without milk, butter and cheese.

Livestock may not have needed much care, but they apparently preferred cultivated fields to open range. Maintaining fences around fields was a constant chore that could not be ignored.

A hundred years later, livestock were still nuisances. In the 1880s Durants Neck and Old Neck were fenced entirely, the residents paying taxes toward construction and hiring Keepers to repair damages and fill hog holes.

In towns, livestock were forbidden by an 1896 law from grazing on streets and public lots. A voluntary Cemetery Society was organized to prevent hogs from uprooting graves in public cemeteries.

Before the Revolution, the colony of Virginia should have been a ready market for farm products, but Virginians generally looked down on their Carolina neighbors and took advantage of their isolation to short-change them. As roads improved and markets opened up, Perquimans farmers drove their livestock further north to the mid-Atlantic: Baltimore, Philadelphia and New York.

Quality didn’t seem to matter much. Salted beef, pork and butter were eagerly traded among colonies. Though lean from travel, livestock sold for 3 to 6 dollars a head, pure profit except for drovers’ fees.

During the last years of the Revolution North Carolina supplied both sides with livestock, mostly on the hoof, since salt for curing was scarce.

Life did not change much for the small farmer during the 19th century, but there were lean years after the Civil War because society was in flux and bad weather destroyed crops. Corn, cotton, and wheat were dependable crops in the 1880s, then later peanuts and soybeans that were also planted after the cotton harvest for livestock feed.

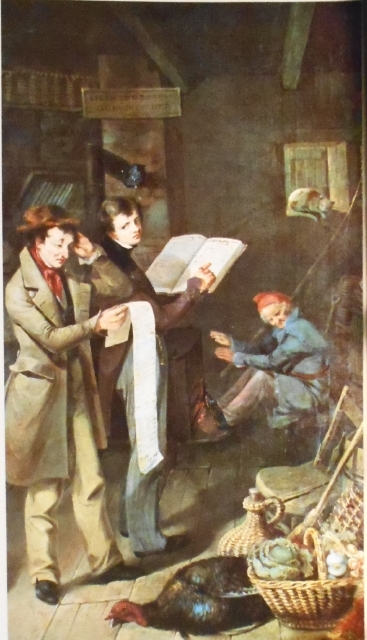

For most of the 19th century, the pioneer system of farming was guided by habit, ignorance and superstition. At the beginning of the twentieth century Perquimans farmers were still shallow plowing with one-horse implements. Commercial fertilizers took the place of green manure and the sturdy two-wheeled Perquimans Cart was still in use.

This broadside is a example of the efforts that states were making to urge farmers to explore new ideas and new techniques throughout the 19th century but farmers responded with little enthusiasm

After 1920, gasoline-powered vehicles revolutionized farming. Agriculture became big business. Farms in Perquimans County consolidated, from almost 1500 farms in 1920 to 350 in the 1980s. Average size increased from about 60 acres in 1920 to 250 in 1982.

After 1920 cotton production almost doubled, and peanuts and soybeans became money crops. Truck farming boomed during the late 19th century because of regular freight routes on the railroad. Grapes became a profitable post civil war industry, and poultry and dairy farms dotted the landscape in the 20th century.

Today, cotton, corn, wheat and soybeans are big crops. Before harvest, crops are chemically dessicated to make mechanical picking more efficient. Cotton bolls pop and fields are snowy along the highways in fall. Automated picking and baling machines light up the fields on dark nights.

Mechanically picked and baled, cotton is ready for transport from a Perquimans field. Photo by FrogsView

As land was cleared and farming became more intense, runoff of chemicals and soil caused a decline in water quality of rivers and streams. People became alarmed at the losses to fisheries, and new farming techniques to protect Albemarle waters came into play.

With financial help from the state, many farmers adopted Best Management Practices on their land to prevent run-off.

State reps meet with farmers in their fields to discuss Best Management Practices that protect water quality. APES photo

Working closely with Cooperative Extension agents, farmers began scouting fields to determine infestations by insect pests. When they adopted Integrated Pest Management, into their operations, the use of toxic chemicals that can contaminate run-off was reduced.

The Quaker Influence

By all accounts, from early settlement, Quakers were a sobering influence on the community.

The Society of Friends were the first active religious group in the colony. A Friends’ meeting in a home near the Perquimans River in 1672 was the first religious service recorded anywhere in the colony. Apparently it was attended by both the religious and the irreligious; the latter smoked pipes throughout the service.

Friends’ Founder George Fox and missionary William Edmundson, who had slogged through swamps (experiences noted above) to meet with the believers found them to be a powerful religious force.

They were a compassionate and caring group (somewhat stiff-necked, too? since they did not share the ferry they owned with non-Quakers).

As a community, they took care of poverty-stricken Quakers to keep them from becoming Chargeable to the Public. They resolved minor disputes during monthly meetings. (In 1735, for instance, an argument over a hogshead of tobacc0 was resolved at a meeting.) Those who tippled would be subject to discourse on temperance.

By 1680 monthly meetings were held in homes on the Little River, Perquimans River and Yeopim Creek. Early in the eighteenth century the thriving community erected several meeting houses in Piney Woods, Old Neck, Wells, and Little River. Annual meetings were described as solid and edifying with many sober people.

Anxious to escape illiteracy, they hired schoolmasters to educate their children in a county where scattered and poor people received little to no formal instruction.

During the 19th century, they established the Friends prestigious Boarding School, later called Belvidere Academy, that emphasized classic literary and religious subjects. Donations for the school came from as far away as New England, Maryland, and England.

Students at the Belvidere Academy, circa 1895, posed in front of original school building completed in 1835. The Historic Architecture of Perquimans County

Undermining Quaker activity was legislation in 1701 that established the Church of England as dominant and authorized taxes to support the clergy. The Quakers, having escaped persecution in England, vigorously opposed the Anglican Church.

There was an upside to this. According to William Gordon, an itinerant preacher, the English vestrymen were mostly ignorant, loose in their lives and unconcerned as to religion, which caused many people to embrace Quakerism.

On the other hand, Gordon also found Quakers to be extremely ignorant, insufferably proud, and ambitious. They were strident in their opposition to Anglicans and ungovernable, he thought, but he very much appreciated their kindness and their invitations to dinner.

After wrestling with their consciences, in 1776, Quaker leadership declared slaves to be inconsistent with the Law of righteousness and ordered members to Cleanse their Hands of them.

Unfortunately, a slave’s freedom was often short-lived. A state statute on the books since 1741 maintained that only the courts could justify manumission. Sheriffs made it a point of seizing slaves as soon as they were freed and selling them at auction. Proceeds from sales enriched county coffers.

Though Quakers strongly objected, legally there was little they could do. Many became disillusioned and uncomfortable with the treatment of slaves in the South and emigrated to free states. Others merged into Southern Methodism.

The PineyWoods Meetinghouse is still active in Belvidere.

(Note: Pasquotank County, east of Perquimans County, also had a sizable Quaker settlement.)

John Harvey and The American Revolution

Massachusetts may have been a cauldron seething against English oppression, but North Carolina had its own firebrand: Perquimans County’s John Harvey, radical anti-imperialist colonial legislator.

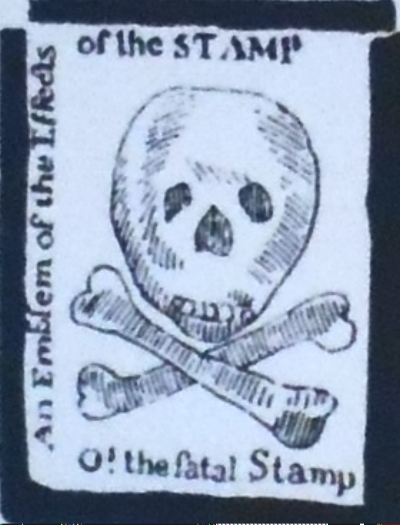

In response to the proposed Stamp Act, John Harvey, with other bold North Carolina legislators, brought out a pamphlet objecting to being Burthened with new Taxes and impositions laid on us without our Privity and Consent and asserted our Inherent right and Exclusive privilege of Imposing our own Taxes. Daring opposition under colonial rule but much in sync with popular sentiment.

Cartoons like this went viral by colonists incensed by the Stamp Act, which effectively required that every newspaper, deed, contract, etc., needed a paid stamp. American Heritage History

Three years later, in 1767, Harvey presented the inflammatory Massachusetts Circular, to the North Carolina legislature. In it, Boston colonists claimed that the British Parliament had no right to tax them, since the colonists had no representatives in Parliament. The familiar, No taxation without representation. Opposition was ratcheting up.

In defiance of the Royal Governor John Harvey then organized an extralegal meeting of assemblymen to protest the Townshend duties by signing a pledge to stop accepting English goods.

He openly clashed with the governor again when the governor refused to seat the colonial assembly so it could choose delegates from North Carolina to attend the First Continental Congress. At issue were The Intolerable Acts, directed against Boston for dumping merchants’ tea.

Harvey declared he was for assemblying a convention independent of the Governor. He moderated this independent convention that elected North Carolina delegates who attended the first Continental Congress.

Harvey openly called the British sanctions against Boston that forbade cod fishing and trading cruel, unjust, illegal and oppressive. He and others organized Perquimans farmers who donated almost 3,000 bushels of corn, 22 barrels of flour and 17 barrels of pork to ease threat of famine in that city.

The letter of appreciation from Boston for the goods shipped in 1774 asserted that the losses, sufferings, and distresses, are really great…not easy to be conceived.

John Harvey died in 1775 from an illness he contracted after he fell from his horse. Despite the loss, Benjamin, with Thomas and Miles Harvey, sons, carried on as representatives to the Continental Congresses.

During the war, Perquimans furnished a full company of continental soldiers and volunteers and militia. While Albemarle counties were spared direct warfare, Perquimans troops saw action at Brandywine, Germantown, Monmouth, Trenton, White Plains and Charleston.

On the home front, the British blockade cut off imports of sugar, rum, and molasses from the West Indies, and textiles from England.

Salt, critical to preserving meat and fish through lean winter times, was in such short supply that at one point 150 citizens plotted unsuccessfully to break open locked warehouses in Hertford to get at the salt.

The blockade was not all negative for the colonies, though. Wearing country clothes, once looked down on by colonists who yearned for ready-made apparel, became a visible badge of loyalty to the new freedom movement and spurred increased planting of cotton.

A lovely water color of the type of simple clothing worn by the lower class in the 17th and 18th centuries. American Heritage History

After the war, Perquimans County delegates to state assemblies, among them Thomas Harvey. consistently supported ratifying the federal constitution.

Ante-Bellum Decades

Heady times, those decades between wars. The energy spent on defeating England and birthing a new country shifted to invention, innovation, profits, and good times.

Canals and steamboats opened the county to new markets in Virginia and further north, though mostly for passengers and produce. The cotton gin dramatically reduced the time it took to clean cotton, and overnight the crop became a cash commodity.

Steamboats like this one pictured on the Tar-Pamlico River could be seen on the Perquimans River

Small-scale manufacturing continued in Perquimans. In 1810, records show 1,800 hides were tanned, 36 stills produced 7,520 gallons of whiskey; 4 fulling mills accounted for 6,500 yards of wool, and 527 looms spun 66,000 yards of cloth, for a total value of $40,762.

Milling corn and wheat continued to be profitable, as were the production of barrel staves and shingles. In 1832 a 50-ton vessel was built at the shipyard in Hertford.

As for recreation, circuses traveling by steamer, were eagerly anticipated for entertainment. The Christmas season was especially busy with parties and dances. Weddings, horse races, parades and fairs broke the monotony of everyday life. For the wealthy there were summer excursions to the Outer Banks.

Religious revivals and the temperance movement brought excitement into otherwise monotonous days. Methodism was embraced, and the Hertford Methodist Church was established in 1855. In fact, southern Virginia and Albemarle counties are referred to as the Cradle of the Southern Methodist movement.

After losing favor during the Revolution, the Church of England shook off its ties with England and rebranded itself as the Episcopal church.

By 1839 a public school system was established by law, but schools were open for only four and a half months a year. Poor roads and distant schools discouraged regular attendance. On the eve of the Civil War, illiteracy rates still ran around 43 per cent.

Academies, forerunners of high schools, were licensed by the state as finishing schools or college prep programs. They were financed by private donations, student fees and occasional fundraising.

Facilities were available to men and women separately, with the promise that women would receive an education that shall fit them for every duty of life. Discipline could be harsh, and memories of school life reflected this treatment.

And so, in spite of ever-present disease and untimely death of infants and young children. In spite of an outbreak of small pox that required guards to enforce quarantines.

In spite of financial panics that squeezed family budgets. In spite of a storm closing Currituck inlet and interrupting shipping. In spite of these troubles, the people of Perquimans County led quiet and simple lives.

Except that there were disparities.

Wide horizons beckoned the wealthy and the plucky, but there was no exit for others.

At one end of the economic spectrum were planters and merchants who had fine educations, owned prime farm land and had comfortable financial backing. They led lives of comfort. For instance, one Perquimans entrepreneur operated saw mills and gristmills, a wharf, a shipyard, a store, in addition to his plantation.

Another, at his death, possessed a spacious house, barn, workhouse, two kitchens, smokehouse, dairy, henhouse and a smith’s shop.

Land’s End was built in the 1830s by Colonel James Lee, one of Perquimans’ wealthiest planters. Photo by Frances Johnston, 1936, Division of Archives and History

At the beginning of the century, eight landholders owned more than a thousand acres each; one owned more than 2,000 acres. The dozen or so plantations in the county prospered by growing and shipping wheat and corn.

Merchants were persons of power in society. On one level they simply provided the necessaries and luxuries of life. On another level, they granted credit and favors and provided shipping for farmers.

During antebellum years there were no more than 20 merchants in Perquimans County. They shipped corn to coastal ports and brought back molasses and salt from the West Indies and, according to shipping manifests, commodities like candles and soap, coffee, rum and gin, tobacco, calico, jeans, whiskey, tea kettles and farm implements.

Somewhere in the middle of this spectrum stood the backbone of Perquimans County: the small farmer. The majority owned 200 acres or less at the turn of the century but this would drop to 100 acres for most by the beginning of the Civil War.

Life did not change much for him. He worked his few acres solo, fished and hunted. Improved farm equipment eased backbreaking labor. And mules, more suited to the terrain, would replace oxen as draft animals later in the century.

With poor roads, few local markets, and no capital, there was little incentive for him to increase yields and improve quality. Thus, there was little academic interest in improving farming methods, and new ways were rejected as book farming even into the decades beyond the war.

At the lowest end of this spectrum were slaves whose harnessed muscle-power provided the comforts for others. As the century wore on, the taut ends of the spectrum would snap.

In 1790 there were fewer than 2,000 slaves in the county, or about 35 percent of the total population, and attitudes toward slaves were comparatively relaxed.

By 1860 about 3500 slaves accounted for almost half (49 percent) of the county’s population. Most households in Perquimans owned only a few slaves, but a dozen or so large landowners held substantial numbers.

There were no dramatic numbers of slaves, or bondsmen, in Perquimans County compared to cotton compounds in the Deep South, but political events and the shift in ratios of master to bondsmen caused tensions to grow.

Despite tensions and runaways many plantation owners clung to the idea that slaves were happy, as shown in this 19th century artwork. They were often surprised when slaves left once they were emancipated. American Heritage History

With the new nation’s independence, slaves wanted their liberty, too. News of slave revolts in the West Indies stirred aspirations. Interracial camp meetings of the religious Second Great Awakening nurtured the black church which became a center for opposition to slavery.

Black hopes for freedom were heightened and runaway slaves, who often found refuge in the Great Dismal Swamp, were a source of growing fear in white society.

In 1802 rebellious slaves in Bertie County to the west planned attacks on settlers to the east in New Begun Creek. The insurrection failed, and one slave was executed in Perquimans County.

The county court called for a patrol that would make a strict and diligent search for weapons. . .disperse unlawful meetings. . .apprehend slaves without proper passes. . .and detain. . .free persons of color (if deemed necessary).

Stiff taxes were levied to pay for the slave patrol, compensate the owner of the executed slave for his loss of property, and rebuild the county jail.

For the most part, slave patrols didn’t work. Members either refused to serve or were lax in their searches and reporting.

Restiveness continued, however, and the county ordered the militia to hunt the large number of runaways, furnishing two gallons of whiskey, a peck of meal and 14 pounds of pork to support the recruits.

In 1831 the Nat Turner rebellion in Virginia struck such fear into citizens that, according to one Quaker, blacks were so severely punished that they rather go any where than to stay where they are persecuted for innocency.

Free blacks were now under constant surveillance and in 1830, the ironically named Free Black Code enacted by state legislators took away their voting rights.

It was just a matter of time . . .

The Civil War and its Aftermath

Perquimans citizens, like most of North Carolina, were reluctant to leave the Union to defend a way of life that most did not share. But they abhorred the idea of being at war with their Southern sister states.

When the state finally seceded from the Union, men of Perquimans County fought and fell across southern battlefields. Two voluntary infantry companies were immediately raised in the county, the Beauregards and the John Harvey Guards.

The Beauregards felt the full brunt of the war in Virginia as General Lee moved on Sharpsburg under heavy fire, with 28 percent of men killed, missing or wounded.

From victory at Fredericksburg, they went on to the Battle of Gum Swamp in South Carolina. More heavy fighting back in Virginia at Bristoe Station, then, after a quiet six months, the final bloody campaigns of the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House, Cold Harbor, and Petersburg.

Near Gaines Mill in May 1864 Captain Skinner from Perquimans County wrote of the constant whistle of the musical Minnie. . .above our heads, the stench of unburied dead on the battlefield, of subsisting on a daily ration of four crackers and a quarter pound of meat. and how dirty the men were, more accurately lousy, after a month without change of clothes.

Sufferings, privations & hardships have been endured such as no modern armies of their countrys have ever been called upon to undergo…but the greater our sufferings now the more glorious will be our ultimate triumph. Unfortunately, Skinner fell in battle in August 1864. By October only 33 men from Perquimans were left in the company, with new recruits from western counties replacing them.

As for the John Harvey Guards, they fought unsuccessfully in the Battle of Roanoke against General Burnside’s Union soldiers who went on to blockade the Albemarle. The Guards were captured, tried and paroled, pledging to sit out the war. They disbanded, but many went on to fight again.

Thirty-eight volunteers from Perquimans helped form Company F of the North Carolina infantry and saw heavy fighting throughout the war, including Pickett’s charge at Gettysburg. Twenty-four of the thirty-eight were killed, wounded or captured.

There were no history-book battles in the Albemarle but everyday life was unsettled and often held terrors for the average citizen. Many still supported the Union and rumor of slave insurrection was unsettling. The county appointed committees to suppress all incendiary movements.

Still, some Union sympathizers managed to form independent bands called Buffaloes who joined federal forces in raids, as did slaves and free blacks, who enlisted in the North Carolina Colored Infantry Units.

Union troops were more intent on destroying bridges along the Perquimans to prevent smuggling contraband to Lee’s army in Virginia than on ravaging a countryside where they had many allies in the common people, though. . .

. . .Federal troops destroyed Hertford’s original float bridge during one raid, and pillaged one plantation on the river during another, with livestock, produce and fence rails destroyed.

Guerilla bands called Rangers, initially authorized by the governor, took it upon themselves to harass Federal troops, prevent slaves from crossing Union lines, plunder, terrify and even murder Union sympathizers.

Their outrageous and lawless behavior angered locals, and Federal troops threatened punitive raids. Citizen outcry was so strident they were dissolved within a year.

As the war dragged on, news of casualties was a continuing source of anguish. Economic distress accompanied loss of family and friends.

Medicine and supplies were smuggled to people on the home front by men who had grown up in the labyrinth of creeks and swamps and knew how to evade pursuers. American Heritage History

In the face of rising prices and scarce supplies one woman wrote: Sure this War is meant to check the profusion in which we have lived & to teach the rising generation economy & the employment of their resources.

Spinners, weavers and stitchers on the home front produced uniforms for soldiers. American Heritage History

The county consistently put the health and safety of its citizens first. It subsidized volunteers and helped support families in need, and continued to collect taxes to pay for county expenses. From time to time, according to the wants of the county, scrip was printed in $1000 increments.

Dedication of monument honoring Confederate soldiers of the County in 1912. Historic Architecture of Perquimans County

If the Civil War represented upheaval, the decades beyond represented cataclysmic change in society.

Now it was time for families to heal and rebuild their lives in a changed world. It was a heroic effort in the face of poverty, the changing balance of race relations, and the political uncertainties of Reconstruction.

An artist’s rendering of a black wedding that would have been forbidden prior to the war. American Heritage History

Loss of slaves and property reduced the standing of the wealthy. Years of poor cash crops caused by bad weather and lack of available labor took further toll.

Yet Perquimans’ population grew by 10 per cent, from 7200 to almost 8000 by 1870. The Town of Hertford, population 500, with a hotel, jewelry store, drug store, 4 grocery stores, 5 general stores, 6 lawyers and 4 physicians, several churches and 2 grist mills kept its place at the core of county life.

And, in an uncertain world, every spring you could count on the running of the fish, an event that brought joy and excitement to townspeople, fishermen and farmers alike.

Man and the River

It was truly an Eden during those early years of colonization. Vast forests primeval of oak and cypress provided furs and meat, tar, pitch and turpentine, boards, shingles and barrel staves.

One can only guess at the abundance of wildlife from reports of fish runs, exports of furs, and court records of bounties. Wolves, wildcats, and crows were hunted for cash, and every taxpayer was expected to kill at least ten squirrels a year in return for two pence a skin.

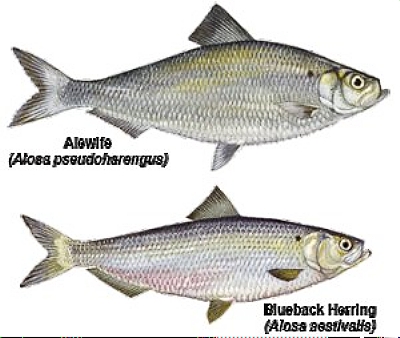

Each spring, river herring, alewife and shad swam in from the sea to lay their eggs in the rich quiet waters of the upper river and its creeks. Here is where their young, along with striped bass born in the Roanoke River, would grow until they were old enough to swim out to sea.

So thick were the running fish, one old-timer, only half-joking, remarked that you could walk across the water on their backs. On river and creeks people would gather with baskets, buckets, poles, lines, to catch and salt and fry and feast on fish (bone and all) and celebrate.

Around Easter time fried shad and herring roe were served at church picnics, and the Perquimans cart, that indispensable, sturdy, two-wheeled all-purpose vehicle, would return from fisheries piled high with herring that often sold for as little as a dollar a thousand.

Stevenson Point, off Durants Neck, may have been the first site of the great seine fisheries of Albemarle Sound in the 19th century. Colossal catches of herring and shad were reported in both Sound and River, with a single haul of 220,000 herring documented at the Point.

As early as 1811, the free passage of fish was recognized as necessary by the state General Assembly. The main channel of Yeopim Creek was staked by four men leaving a third of the channel open for migrating fish.

By 1851 the use of seines within a mile of the mouth of the Perquimans River between sunset on Saturdays and midnight on Sundays was prohibited, and seines that blocked more than two-thirds of the river channel were never allowed.

Seine fishing was a large complicated and expensive undertaking. A seine more than 2000 yards long and 18 feet deep was laid about a mile off shore, usually by men in two boats.

When the boats returned to shore, ropes were attached to capstans, each turned by six horses, which gradually brought the net ashore where women and boys were waiting to trim, salt and pack the fish for transport.

Pound nets were smaller and easier to manage.

For more than three hundred springs since settlement this passage of the herring played out. Then the herring stopped coming.

By the 1880’s catches were down, prompting the federal government to study fishing practices, hence the photographic documentation included in this Albemarle series.

But it wasn’t just over-fishing that began the decline.

- Ditches and canals in farm fields speeded drainage into creeks, disturbing once quiet pools where young fish could find food.

- Powerful, fast-acting chemical fertilizers and pesticides were introduced.

- Nutrients from chemical fertilizers in runoff promoted algal blooms that deplete dissolved oxygen levels and cause fishkills on hot summer days.

When the railroad arrived in the 1880’s, lumber companies burst on the scene. By 1920 forested land in the county was reduced by half. Fifty years later, massive areas in the county would again be lumbered, ditched and drained for agriculture.

There was always hope the herring fisheries would revive, and some years were good and spirits would rise.

But water runs off quickly when low-lying timbered land is cleared. It does not seep slowly through swamps and cleanse itself. Pools for spawning fish become turbulent and muddy.

As towns grow and roads are paved and industry arrives, pollutants are discharged directly from pipes or sewers. This point source pollution contains toxic chemicals and bacteria.

Perquimans County, still mainly rural, with no heavy industry, escaped the worst of this type of pollution. But changes to the land over time took their toll.

And so, by 2006, the herring fishery across Albemarle waters was stilled and a time-honored tradition had disappeared.

They may not come by the millions today, but there are still fish out there. Photo by S. Taylor APES publication

Preserving a Way of Life

Wise County Commissioners have been wary of inviting heavy industry into the Perquimans countryside. So this rural area has been spared the usual paths of modern progress and grave insults to water quality.

But juggling economic needs with environmental protection and quality of life is a delicate act. During the late 20th century, there was a great push on several fronts to educate people about protecting our priceless environment.

Congress passed legislation to initiate studies on the nation’s estuaries. In North Carolina the Albemarle Pamlico Estuarine Study (APES) brought state officials, scientists, and public citizens together to produce a guide to protecting the future of the estuaries.

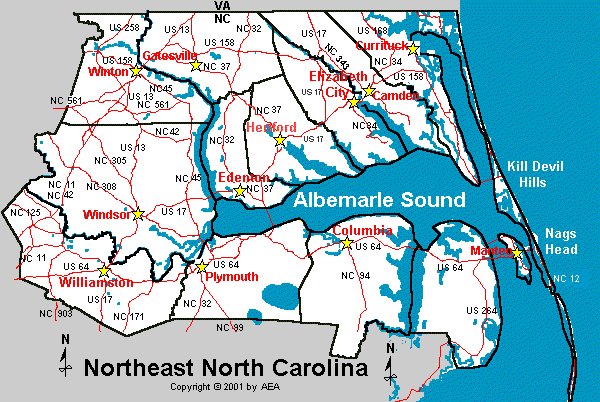

Map of eastern North Carolina showing the general APES study area, including the Albemarle and Pamlico Sounds. Credit: NC Land of Water

Grass-roots activists formed the Albemarle Environmental Association (AEA). Major issues successfully tackled were a proposed hog farm, a landfill in wetlands, a hazardous waste incinerator, a mega-marina, and a Navy landing field.

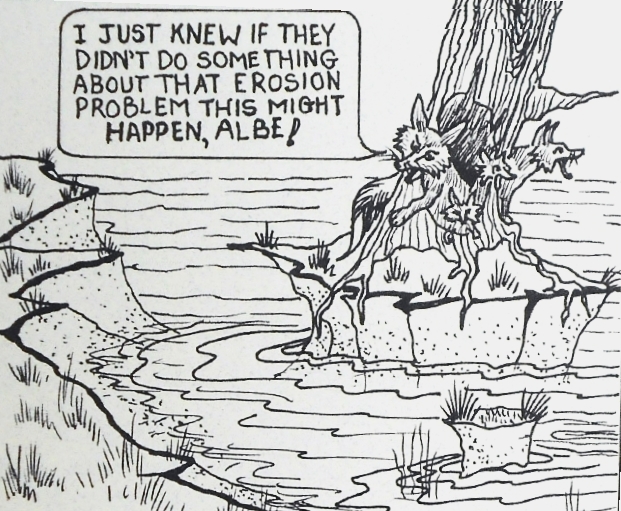

As part of its public education program AEA published newsletters and flyers. This is a page from a booklet titled Nature’s Caretakers, in which a foxy family rallies citizens to action. Artwork by Elaine Roth

Field trips and group canoe excursions led AEA volunteers to compose an interactive Green Guide to the Albemarle that features points of interest in each county, canoe trails and maps. Go to AEAontheWeb for more information.

AEA’s field trips on streams and rivers gave the impetus for the interactive Guide to Albemarle Waters included on its website. AEAontheWeb.org

Under the auspices of Streamwatch, citizens and school children tested local waters to gather and record chemical and physical data.

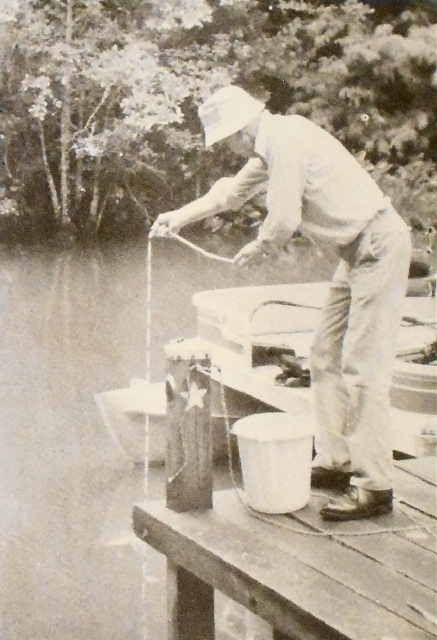

Volunteers often tested water from their own docks.

Volunteer George Hilborn tests water quality in a canal flowing into Albemarle Sound from the Holiday Island community in Perquimans County

The idea of Ecotourism was embraced. Vacationers who stopped here could find beauty, tranquillity, and rich history in a setting that exists nowhere else in the country.

Ecotourism can protect communities and natural areas from unwanted change and put dollars in people’s pockets. Hiking, biking, boating and fishing can boost the economy and, at the same time, tread lightly on land and water because little infrastructure is needed to support them.

The twelve-mile canoe route along the upper Perquimans River is a lovely excursion that introduces canoeists to the winding and scenic river. Photos, description, directions and maps for this canoe route, as well as for the Yeopim River and Creek trips can be found on AEA’s Green Guide to the Albemarle.

There is always a great blue heron on the Yeopim River and Creek, and sometimes an osprey or two.

Some canoeists have called the creek a jungle cruise because trees hang over the stream in places and wildlife can make surprise appearances. AEA photo

A walking tour of Hertford’s historic homes along the river, and a stop at the old corner drug store for a pimento cheese sandwich or an ice cream cone makes for a pleasant afternoon diversion.

The Newbold-White House, the oldest brick house in the state, sits high on the banks of the Perquimans River and tells an eloquent story of colonial farm life. Built by a prosperous Quaker family in 1730 and authentically restored, it was once a seat of county government. Open to the public, it stands as gatekeeper of historic times.

Seasonal gardens feature herbs and flowering plants, and muscadine and fox grapes still grow in the old vineyard, thanks to care by faithful volunteers.

Batts Grave and Challenges to Come

On old maps there is a small island of several acres south of Yeopim River called Batts Grave. During the 17th century the island could easily accommodate a house and a small farm and fruit trees.

The island called Batts Grave is shown as a small oval in the Sound just south of the Yeopim River in this 1733 map by Edward Moseley

Nathaniel Batts, the owner, may have been a recluse when he died on this island, but he was a colorful presence in the Albemarle during the mid-1600s: explorer, fur trader, pardoned murderer, friend to both Indians and people in high places, serial debtor and swindler.

Batts Island does not appear on today’s maps. It has been eaten away by wind and waves and a rising tide. It is only one example of changes to come in the Albemarle. Rising sea level will eventually affect low-lying Albemarle lands, and future planning needs to include a resilient approach to climate change.

We cannot bring back lost nursery areas for fish, or recreate the primeval forests or massive swamps that sustained our ancestors. Nor can we push back rising tides. But we can plan for an economy that is resilient, one that will maintain that special quality of life found here, and one that will weather rising tides.

Windmills that take advantage of steady winds and solar arrays that take advantage of long hours of sunlight can co-exist with prosperous farms and help an economy grow.

But it will be up to individuals, non-profit groups, local and state governments to work together to protect our waters and manage our land for the health and well being of those who visit and dwell in this land of beautiful women.

There will always be room for one more turtle on the log.