Here was a good country. . .

. . . where crops were heavier, forests deeper and trees taller. In the spring the herring and greater fish also swam up in schools to spawn,” explorer Ralph Lane wrote in 1586.

Here was rich territory to explore. Like every other waterway in northeast North Carolina, the Chowan River offered virgin forests, deep swamps, and rich soil that sustained original civilizations for centuries and provided for settlers who arrived later.

Vital Statistics

The Chowan River is more than two miles wide when it finally spills into Albemarle Sound. On a gray, windy day its waters may be dark and choppy, its waves ruffled with white caps that roll against a lonely skiff. But when the sun is setting against a clear sky and the wind is whispering, the river becomes a looking glass for the land.

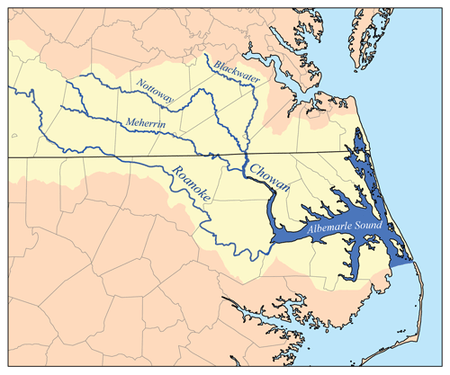

Far north in Virginia the river is only a trickle in wetlands. Gathering strength and rising as dark coffee-colored streams stained by tannins from swamps, Virginia’s Blackwater and Nottoway Rivers eventually merge to form the Chowan River at the Virginia/North Carolina state line.

A third river, the Meherrin, also rises in Virginia and flows southeast until it joins the Chowan River in North Carolina. In all, about 70 per cent of the Chowan River’s flow comes from Virginia.

The Chowan River and its tributaries. Four counties lie along the river, Gates and Chowan on the east, Bertie and Hertford on the west. Map by Elaine Roth

The river’s drainage basin is vast. It is formed from networks of streams (some 760 miles in North Carolina alone) that feed larger tributaries that drain about 4,800 square miles of land in North Carolina and Virginia.

Like the Roanoke River, the Chowan contributes millions of gallons of fresh water daily to Albemarle Sound.

The map below gives an overview of the river as it flows toward Albemarle Sound.

Note the three tributaries from deep in Virginia that combine to create the Chowan River. The confluence of the mouths of the Chowan and Roanoke Rivers has dominated the history of Bertie County, on the western shore of the Chowan River

The river itself is about 50 miles long, narrow and energetic in its northern reaches. As it skirts Holiday Island, it widens and makes a leisurely arc to meet Albemarle Sound near Edenton.

Large, awe-inspiring swamps of tupelo-gum and cypress fringe much of the river’s northeastern shore and may extend far inland. Chowan Swamp is one of the largest in North Carolina.

Chowan Swamp, a rich wilderness. “Knees” are typical of cypress trees, one of the dominant trees in the area

Creeks may be lined with wild rice and arrow arum and rare wild cordgrass. These waters in the upper reaches are mirrors of wilderness, but determined paddlers can access them through blackwater streams that filigree the area.

Migratory songbirds find homes here, as do black bear, bobcats and river otters. In spring, fern fiddleheads poke through moss carpets, tree frogs call, and baldcypress sprout fresh greenery.

A paradise to paddle, rich in wildlife, the swamp plays an important role in maintaining the health of the river. Water from land journeys leisurely toward the river through spongy wetlands that cleanse it of pollutants.

Thanks to dedicated work by The Nature Conservancy, Union Camp Corporation, and Georgia Pacific, 11,000 acres of these wetlands inland and along the river are now protected.

The western shore of the river is dramatically different. Its steep cliffs speak of colossal sculpting of the earth’s surface through geologic ages. South of Colerain, bluffs as high as 50 feet or more rise, part of the Suffolk Scarp, thick with beds of muds, sands, clays, with fossils that tell incredible stories of past ice ages and rising sea levels.

At one time, sea level was so high, the ocean lapped at this bluff. During ice ages, sea level was so low the shoreline extended way out on the continental shelf.

The lands of the Chowan River are no strangers to climate change.

Today the Terrace is being eroded by winds from nor’easters and cyclones and undercut by storm surges. In places, gnarled old cypress trees, many now submerged, hold waters back and prevent erosion, creating headlands along the shore.

Erosion can cause loss of artifacts from original settlers now being unearthed.

Looking north from the Wicomico Terrace along the river. Note the scalloping of the shoreline, influenced by the growth of cypress trees, many of them drowned. Photo by S. Riggs

These cliffs from time are a stunning backdrop to an ambitious eco-tourism venture. Bertie County is partnering with state and non-profit agencies to reclaim waterfront and wilderness for the public.

Wilderness along Salmon Creek acquired by the NC Coastal Land Trust was folded into land conserved by Bertie County for eco-tourism. Portfolio Coastal Land Trust

Here, where the Chowan River begins, lies a 2200-foot-long sandy beach lapped by shallow, calm waters. Fourteen hundred primeval acres will features water sports, picnicking, hiking, and primitive camping.

Algonquin Heritage

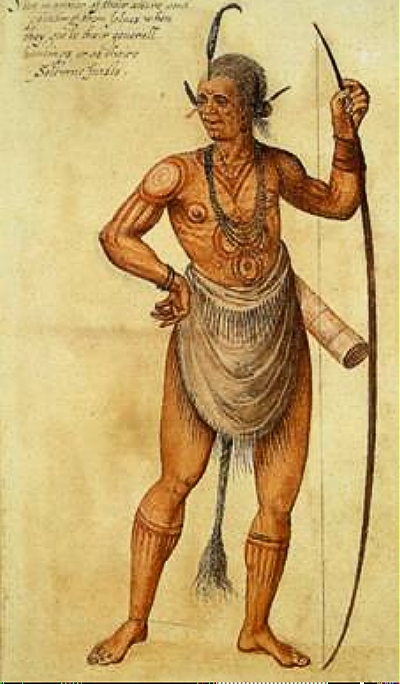

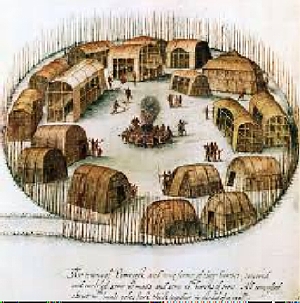

For centuries, Algonquian tribes lived along the banks of the Chowan River, Wapeamoks on the west, Chowanokes on the east. Oak-hickory forests, fertile soils, and productive waters yielded a fine living for these tribes.

With some 19 towns and 700 warriors ready for battle, the Chowanokes were considered the most powerful tribe in the area.

In a move that would scar relations forever and presage the demise of the tribe, Ralph Lane, who commanded Sir Walter Raleigh’s expedition to the New World, captured the chief of the Chowanokes and held him for three days, then took his son hostage. Skirmishes provoked by both sides continued unabated.

By the following century, the Chowanokes would enter into a treaty with the Lords Proprietors of England, who now “owned” the land, a gift from King Charles II. They would submit themselves to the Crown of England, perhaps hoping for impartial treatment. A futile strategy.

Tensions grew. Treaty violations were frequent as more settlers claimed homesteads. By 1676 the Chowan River War, rarely mentioned in history books, erupted. After two years of fighting, the Chowanokes lost their land and a new treaty relegated them to twelve miles along Bennetts Creek.

Eventually, even this land was lost and members of the tribe assimilated with outside communities.

The memory of their presence lives in the names of the rivers they fished.

Rural Heritage

Settlers came relatively late to North Carolina. The Outer Banks, that narrow strip of land protecting North Carolina from the Atlantic Ocean, barred early ships from navigating Albemarle Sound. So the first settlers sought a relatively easy voyage to the New World through Chesapeake Bay and settled instead in Virginia. . .

. . .until an adventurous Virginia politician and professor, John Pory, explored the river in 1622 and reported on this very fruitfull and pleasant countrey, full of rivers, wherein there are two harvests in one yeere.

Colonists began to migrate from Virginia. Traders and farmers in search of good land for growing tobacco and corn, began to slog through swamps, and float down the river. As they found good land, they settled along its banks.

In 1708 another British visitor wrote: The fame of this new discovered summer country spred through the other colonies and in a few years drew a considerable number of families thereto, who all found land enough. . .

By 1780 most settlers were working farms of 200 acres or less, with an average of 16 head of cattle. Fewer than two per cent had lands totaling more than 2,000 acres.

Land and water sustained them. At first they took lessons in survival from Indians. They felled trees to build homes, they fished, farmed, raised hogs that were allowed to go wild, and hunted and traded. Their impact on the environment was minimal. The abundance of the land was not diminishing.

This has been called the last foothold in America of the English yeomen who came to make their living off the land.

For centuries these Chowan River people cultivated tobacco, corn and cotton on flat farm lands adjacent to the river. Later, peanuts and produce, including watermelons and cantaloupes were added to the mix. To this day, Rocky Hock melons, as they are affectionately called, are the best tasting you will ever find.

Herring on their annual spawning run. When salted, they could provide food for an entire year. Photo by John Burrows

Families have lived comfortably along the river since those early days. Conservative, clannish, abhorring debt or obligation, they are known in Chowan as proud and independent people.

A count during the mid-20th century revealed 895 farms averaging 81 acres operating inland and along the river, with 700 growing peanuts and produce. Only four farms over 1,000 acres existed. Later in the century corporate agriculture would begin buying up family farms across the Albemarle.

New and different crops are being experimented with today. Clary sage, a fixative in fragrances and an essential oil, is beautiful when fields of it are blooming along State Route 17 in Bertie County.

Getting Around in a Roadless Wilderness

In a world of dark thickets and tangled swamps, landings along the river with names like Black Walnut, Willow Creek, and Goose Pond invited the weary traveler to rest. They were, literally, lifelines for settlers isolated in a wilderness that would not have reliable roads for a century or more.

Every household owned a boat, and ferries did brisk business on rivers and creeks. In fact, Parker’s Ferry on the Meherrin River operates today. It’s a leisurely ride that takes the traveler back in time.

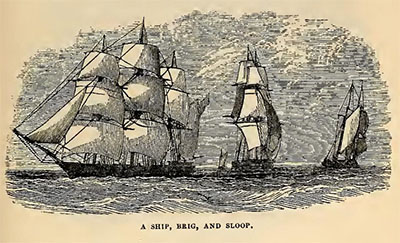

Eventually, sailing ships, tugs and barges, began to navigate the river and its shallow tributaries. Edenton and other Albemarle towns did a thriving shallow draft shipping business. Barges carried off produce, lumber, fish in exchange for manufactured goods, rum and sugar from England and the West Indies.

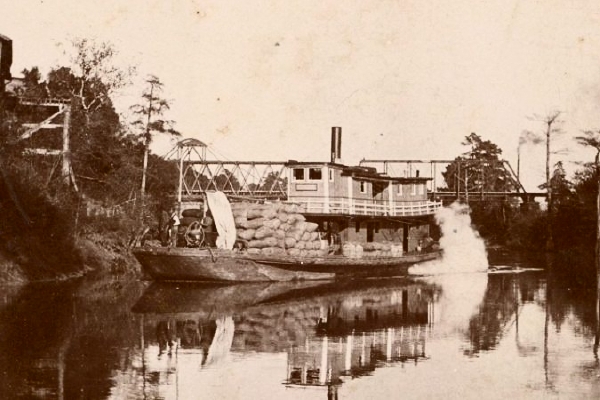

By 1831 the first steamships began regularly scheduled trips up the river and across the Sound, dispatching passengers and freight for almost 100 years.

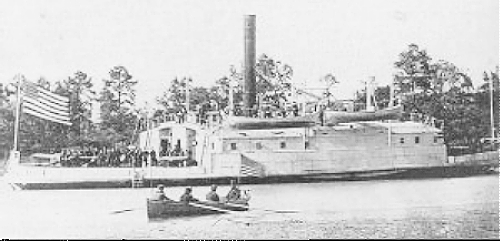

The Keystone (A.S.N.) operated on the Meherrin, Wiccacon and Blackwater Rivers and Bennetts Creek 1905

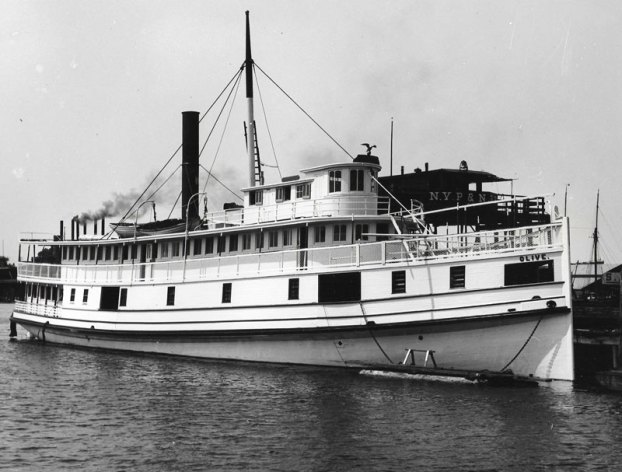

Steamboats ferried folk south across the Sound from Edenton to Plymouth, and the Albemarle Steam Navigation Company (A.S.N.) offered service from Edenton to Franklin, Virginia.

The Steamship Olive regularly travelled Sound and Rivers until it was capsized by a violent line squall and had to be replaced

Show boats were eagerly anticipated as they floated from town to town along the Chowan River. They would stop for a few days or as long as a week at ports from Murfreesboro in the north to Edenton in the south. They brought entertainment and a glimpse of glamor from an outside world, and they often used townspeople in the revues.

In December 1881the Norfolk-Southern Railway reached Edenton and steamers were slowly replaced by rail and roads.

The railway bridge crossed Albemarle Sound in 1910. Then, in 1927 a 1-1/2 mile toll bridge spanned the Chowan River. It was hailed as freeing the Lost Provinces of the Northeast from Virginia’s economic domination.

In 1938 a highway bridge across Albemarle Sound sealed the closing of the venerable Mackey’s Ferry, headquartered on the south shore of Albemarle Sound. It had been a prosperous enterprise that had taken passengers and freight across the Sound since before the Revolution.

Sadly, when the railway arrived, sharp speculators came with it. They bought up standing timber, worth $1.50 a thousand board feet for only 25 cents a thousand board feet. Then they stripped the land at their leisure. The locals realized very little profit from one of their most precious resources.

The Town of Edenton

The Prettiest Town in the South, that’s what Edenton is called, and for good reason. The town is inviting to explore, with lovely old homes and gracious Southern hospitality.

By mid-1700s Edenton was a bustling harbor near the mouth of the Chowan River. It was the first capital of the colony, from 1722 to 1743.

As the official Port of Roanoke, with direct access to the Atlantic Ocean through an inlet in the Outer Banks, the town was a hub for trade. Two shipyards thrived here before the Revolution. In one year 1771-72 142 ships cleared the port, mostly two-masted brigs bound for Europe, others heading south to Ocracoke Inlet for brisk coastal trade with the West Indies.

During a single five-year period in the 1770s, ten million oak staves, 16 million shingles, thousands of hogsheads of fish, tobacco and corn, and over a thousand deerskins left this royal port, raw materials from land and water in exchange for rum, sugar, molasses and linen.

These are staggering numbers. Edenton was, after all, barely a town during the first part of the century. William Byrd, a wealthy Virginia planter, visited the colonial capital in 1728 and found a settlement with only 40 or 50 houses, with neither church, chapel, mosque, synagogue, or any other place of public worship.

The people had no ambition, he wrote, and they considered a brick chimney on a house a sign of extravagance.

But the town grew rapidly as more and more people with education and ambition settled there. From its first house built in 1714 by Edward Mosely, surveyor for the colony, it grew t0 165 houses in 1777.

Ship captains and planters, politicians and public servants, built architecturally fine buildings that reflected the growing wealth of the community.

After a hurricane closed the inlet in 1795, Edenton lost some of its pre-eminence, but not its charm.

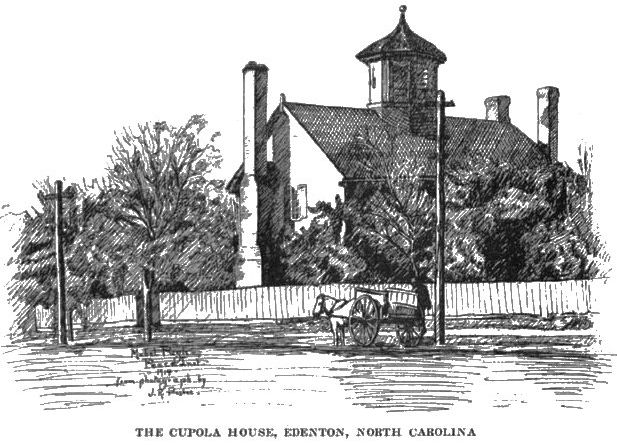

This century-old artwork depicts the Cupola House, built in 1758 and considered the finest example of a southern Jacobean home built of wood

In one of the earliest preservation efforts in North Carolina, women of Edenton formed an association in 1918 to rehabilitate the Cupola House, one of the state’s oldest homes. Today the Cupola House Association maintains the landmark and volunteers maintain the gardens.

On the old streets of Edenton, most within walking distance of the water, are a dozen or more well preserved houses of colonial vintage and dozens more ante-bellum residences.

The architecture, the ambience, and easy going friendliness contribute to a thriving tourist industry that celebrates the history of the town and supports the population.

Part of that history includes the old Edenton Cotton Mills, once the town’s largest industry after the Civil War and into the 20th century and the largest textile plant east of Tarboro.

Cottages that once housed former employees have been renovated and a small community has evolved within the town.

The Edenton Cotton Mill, pictured here in 1900, provided a market for cotton growers in the decades after the Civil War

The Revolution: Patriots of Edenton

By 1776 the bustling city of Edenton provided refuge for American ships during the Revolution. The Chowan River became a vital supply line for Washington’s army.

Angry over England’s oppression, colonists were ready to retaliate. The colonial Navy was no match for British frigates, so patriotic sailors and merchants worked the high seas, and suddenly, England found herself financing the enemy’s navy.

Here is how it played out. Captains skilled in smuggling organized fleets of privateers (smugglers legally sanctioned by colonial government) to seize British merchant vessels and their cargo.

Naturally, British captains would bring these cases of plunder to court, hoping for just resolution. Trouble was, the British court system had collapsed and been handily replaced by colonial courts.

With little deliberation, courts routinely ruled against the British. Colonial captains, who were given leave to keep the booty, turned most of it over to the war effort. And that is how England helped finance the rebel navy.

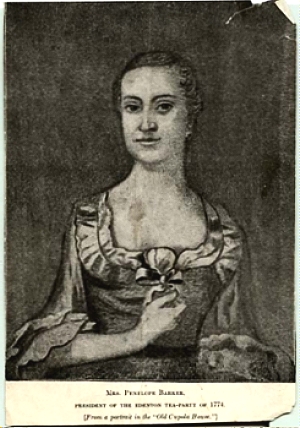

Edenton’s women were no less patriotic. They aimed to empty the pockets of English merchants. Penelope Barker, a strong and capable woman who had outlived three husbands, organized a group of 51 women in October 1774 to sign a resolve to boycott English imports and support the North Carolina Provincial Congress.

The women pledged to do every thing that lies within our Power to testify our sincere Adherence to the Peace and Happiness of our Country. They sent their resolve to the Crown.

This was life-changing action for colonists who by now relied on tea, cloth, and household goods delivered by British ships. The pledge also appeared in the Virginia Gazette, a Williamsburg publication, which meant the news would travel throughout the colonies and give ideas to other communities.

In Mrs. Barker’s words: Maybe it has only been men who have protested the king up to now. That only means we women have taken too long to let our voices be heard. We are signing our names to a document, not hiding behind costumes like the men in Boston did at their tea party. The British will know who we are.

And so they did. By January 17775 the resolves appeared in a London newspaper, along with a lampoon called A Society of Patriotic Ladies that viciously satirized the women and their patriotic action.

Today, this event is known as the Edenton Tea Party, and an ornate bronze teapot is mounted in the village green across from the County Courthouse. It is a tribute to the courage of this group of women and an example of early patriotism.

Many consider the Edenton Tea Party to have been a landmark in the history of women’s activism in America. The Barker House, where Penelope Barker lived, is open for visitors.

The area escaped relatively unscathed by the war, though, as the story goes, at one point colonists were panicked by news that the British intended to burn the town of Edenton. In a trice, townspeople en masse crossed the Chowan River on barges, emptying the town.

They then hiked the trail, 15 miles or so, to the town of Windsor, where they enjoyed the hospitality of fellow colonists for a week. When the British never showed, Edentonians returned home. Today, that trail is well traveled US Route 17.

Antebellum Years: Cotton is King and Plantations Prosper

In 1787, the year of the Constitution, little cotton was grown. Most people scrabbled for a living, growing basic necessities and some tobacco, peanuts and corn for trade. The few who owned large parcels, began to set aside acreage to grow crops for trade. After experimenting with tobacco and rice, cotton became the crop of the future.

A modern cotton field, growing robust hybrid cotton that is harvested only once a season. Photo by aheronsgarden

Thirty years later, plantations had become a profitable business model in the Albemarle, owned by aristocratic, politically active planters and worked by slaves.

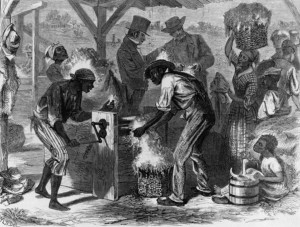

Eli Whitney’s cotton gin crowned King Cotton. Now a slave could clean seed from fifty pounds of cotton in one day, instead of only one pound by hand.

Artwork from Harper’s Weekly periodical, depicting the workings of the cotton gin depicted through northern eyes

Cleaned cotton was pressed into bales and shipped off.

Across the South, old growth forests were stripped, ploughed and planted. Seeds were set into the ground in March in rows three to five feet apart, and from April to August the fields were weeded.

By August, cotton bolls with sharp points that can be so hurtful to pickers encased the round, fluffy clumps of cotton and its seeds. . The entire slave community was enlisted for picking, filling sacks as quickly and as often as they could. In general, a slave was expected to work ten acres and pick about 200 pounds a day. There were several crops a season.

Late nineteenth century photograph of cotton picking, which had not changed much since ante-bellum years. Archives of NC

After the War of 1812 the cotton boom kept textile mills of New England and England humming. Easily stored and transported, cotton helped fuel the Industrial Revolution in the United States and Great Britain.

By 1860 slave labor in the South was producing two-thirds of the world’s cotton, 2 billion pounds of cotton a year. . .

. . .which gave a false sense of security to southern planters. Now that Cotton was King, the North needed this raw material from the South too much to ever consider threatening slave states. . .

. . .except, the South needed manufactured goods and the trappings of a comfortable life from Europe and the industrial North. And Southern planters were borrowing money from Northern banks.

At the same time, domestic slave trade was becoming highly profitable. By 1808 slaves could no longer legally be brought into the United States from other countries. Slaves traded among states became a valuable commodity.

Artist’s rendering, Slaves Waiting for Sale, dressed up for buyers who would be waiting to dicker outside the quarters where the slaves were housed

In northern Virginia and Maryland, where wheat replaced tobacco on farms, surplus slaves were sold off. In the early days slaves were sent to the Carolinas, then eventually farther south. Slave auctions were held every day. Families were separated routinely.

Some of these slaves were transported to counties on both sides of the Chowan River.

Artist’s rendering, After the Sale, Slaves Going South from Richmond to St. Petersburg, from there to points south

Gates County, directly south of Virginia, prospered. Tobacco thrived in its soil, Virginia markets were nearby, and slaves for working crops were easily accessible. By 1860, almost half the population in Gates County were slaves. Planters built sizable homes here, Buckland in 1795 and Elmwood in 1822.

As a result, the area around Gatesville became a thriving commercial center with grist mills and saw mills and general store. (More about the twists in Gatesville’s economic history below.)

By 1860, in Bertie and Chowan Counties, slaves made up nearly 70 per cent of the population. Since the Albemarle had no major port, most slaves were brought from Charleston, South Carolina or Virginia.

Let’s take a brief look at three plantations and their owners who prospered in the vicinity of the Chowan River. Although plantation acreage in eastern North Carolina did not rival that of neighboring states, the model was similar

In many ways, Hope Plantation in Bertie County, and its ante-bellum owner, David Stone, are reflections of plantation society in eastern North Carolina.

Its thousand acres were a self-sufficient community dependent on slave labor, with grist mill, still, saw mill, blacksmith, cooper’s shop, and houses for spinning and weaving. Cattle, sheep and horses were raised in pastures, hogs roamed the woods, while forests produced timber for the saw mill.

David Stone was a former governor of North Carolina, US Senator and US Representative, and Justice of North Carolina Superior Court. During his tenure in politics he supported advancements in agriculture and industry and education for both sexes.

Stone also operated another plantation near Raleigh and owned a total of 137 slaves, which, according to knowledgeable sources, the family freed before the Civil War.

Today, Hope Plantation is restored as a museum and open for visitors

Hayes Plantation on Albemarle Sound near Edenton is a private home today, with a working farm of a few hundred acres, far fewer than the 1500 acres in 1860 on which mostly corn was grown .

It is listed in the National Register of Historic Places and is of interest as a fine example of palladian architecture built in 1814.

Its owner, James Cathcart Johnson took a direct hand in designing and constructing the manor house, employing contractors, using slave labor as brick layers, plasterers and artisans. He negotiated terms for hiring slaves with their owners who, in turn, profited from their slaves’ work.

Once freed after the Civil War, many artisans who had fine construction skills continued to work independently. Their expertise in building trades was universally recognized, but their pay was typically shorted.

Built in 1838, Scotch Hall was the largest plantation complex in Bertie County, extending from Salmon Creek in the west to Albemarle Sound. George Washington Capehart owned more than 8,000 acres that were worked by more than 300 slaves and realized an annual income of 100,000 dollars. The Capehart fishery was one of the most profitable in the area.

George Higbie Throop, who had been a tutor for the Capehart family, wrote a novel, Bertie, that pictures daily life on the plantation: the visits, the parties, dining, fishing, hunting, the thrill of mail delivery, festivities at Christmas, including slave celebrations, and vacations at Nags Head.

The privations of the Civil Wat would exact a toll on the plantation, and by 1870 the assets of the Capehart family were reduced to $12,600.

And what of the people whose toil created prosperity for plantations?

An 1860 map shows Chowan County to have the seventh highest ratio of slaves to free persons in North Carolina.

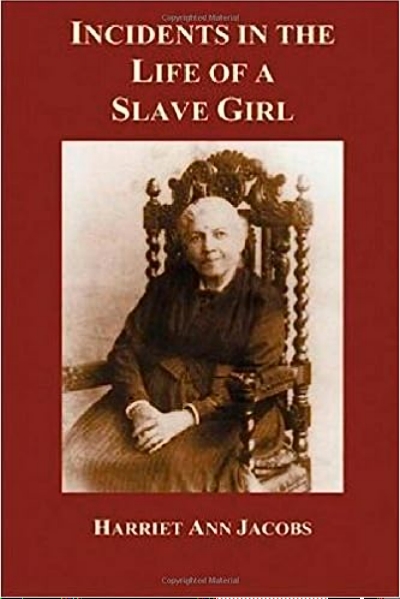

There is no more compelling description of slavery and its moral degradation of Southern society than the book by Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Most of what was published during and after ante-bellum years was written by Northerners who rarely got the full story and often relied on propaganda from the planters.

As Harriet Jacobs unspools her personal story, she describes life under slaveholders with its gratuitous cruelty. She offers deep insights into the corrosive effect of slavery on family relationships, and how laws and policies (and Nat Turner’s rebellion) made life hellish for slaves.

Jacobs had the good fortune to learn to read and write when she was young. She knew her Bible and was acquainted with the philosophy and literature of the 19th century. She is a lively and accomplished writer, and her book is rich with detail and drama.

After years of torment by her master, she went into hiding in an attic, until, with help from free black pilots and dockworkers, she managed to escape to the North, though still shy of the freedom she so desired.

She spent the rest of her life in the north, fighting for social reform. The house where she was kept hidden for seven years is on the walking tour of Edenton.

Civil War

Two impressive relics of the Civil War overlook Edenton Bay today. What stories they could tell of battles!

In 1862, Captain William Badham, Jr. and others recruited men from surrounding counties to organize the Albemarle Artillery, eventually designated Company B, Third Battalion, NC Light Artillery. More familiarly, the company was known as the Edenton Bell Battery and would serve in several battles.

Although the company of men were willing to fight, they did not want to be consigned to the infantry. They needed artillery. In a gesture of solidarity, bronze bells were donated from courthouse and churches, melted down and cast into four bronze cannons by a foundry in Richmond Virginia.

The Battery saw action on fronts across the South. Overlooking Albemarle waters today are two of its howitzers, captured and on loan from Shiloh Military Park and Old Fort Niagara. The other two are lost to history.

Once Roanoke Island fell to Union troops in 1862, the town of Edenton, plantations, fisheries, and settlements along the Chowan River were raided regularly. Union troops seized stores of food and cotton and burned storehouses to cut supplies to Confederates.

Unfortunately, often a family’s stores of meat and grain were destroyed, leaving them to face starvation. Since able bodied men were gone to war, only young boys, women and old men were left to mount a defense.

Particularly frightening were the marauding native Buffaloes, deserters or fugitives who stirred up slaves and became effective spies for the Union because they knew the lay of the land so well. The higher, dryer, western shore of the river saw most of the action: Colerain in Bertie County, and Murfreesboro and Winton in Hertford County, for example.

Gerald W. Thomas writes in Divided Allegiances that troops set fire to John Garrett’s farm buildings that held “a large quantity of meat salted for the confederate government…between 150,000 and 200,000 pounds of pork, 270 barrels of salt, 10,000 pounds of tobacco, 32 barrels of beef and other stores.”

By order of the government, the Confederates themselves burned stores of cotton to keep them out of Union hands. This wholesale destruction of property along the river caused great hardship to communities, and some families never recovered.

The River itself was strategically important to the North.

As part of the Union Plan to destroy the Wilmington-to-Weldon Railroad and cut off Lee’s supply line to Virginia, Union troops sailed north up the Chowan River, then headed west to Welden.

Image of the Commodore Perry gunboat that raided the town of Winton in 1862. US Naval Historical Center, Washington DC

By the time the ships reached Winton, so the story goes, Confederates had discovered their plan and were hiding in the woods to ambush them. They sent a slave girl to tell Union troops that the rebels had already fled in fear of an attack.

The plan might have worked except that Union sailors spotted a glint of sunlight on a musket barrel. Union ships regrouped, burned Winton to the ground and the troops continued their trek west to the railroad at Weldon. In a twist of irony, they may have faced the Edenton Bell Battery in their offensive.

After the war, the entire Albemarle suffered economic hardship. Fortunately, with the abundance of fish in rivers and Sound, together with hard-scrabble farming, most people were able to cobble a living against the odds of economic upheaval.

The Mighty Herring: King of the Water

Since colonial times, fishermen swept the Chowan River from March to May for river herring, shad, and rockfish (striped bass).

These fish journey annually from sea to coastal waters in the spring, teeming upriver in colossal numbers to spawn, before returning to spend the rest of the year at sea.

Their arrival in vast numbers meant an abundance of good eating for the rest of the year. Colonists quickly learned fishing techniques from the Indians.

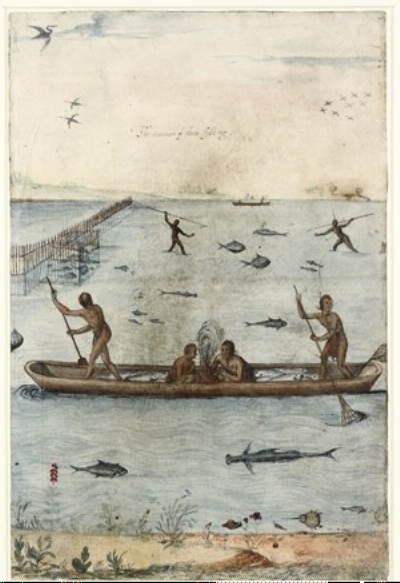

The Manner of their fishing, composite drawing by John White c.1585 showing brush weirs, spears and nets and a variety of fish including a horseshoe crab, whose eggs were eaten

By 1762, an Irishman named Richard Browning had introduced herring fishing on a commercial scale. For two centuries herring brought prosperity and profits to the Chowan River and Albemarle counties.

Pound nets, gill nets, or huge seines, some a mile long, would lace the waters to trap herring, shad, sturgeon and rockfish as they swam upstream.

Once the catch was in, women would clean and prepare the fish for sale.

Once steam power permitted use of larger seines, commercial fishing quickly spread down the river and out into the Sound.

Steam power turned the capstans that hauled in large seines. When seines were smaller, men or mules would do the laborious work

By 1830 the herring industry was booming, with 28 large fisheries on the Sound and River that required 5,000 hands and 200 vessels. In one haul 45 tons of rockfish were taken. A single historic catch in 1890 at Bandon (now Arrowhead Beach) yielded 1,000,000 herring.

Even into the 20th century, herring fishing was still part of the fabric of the community, with two large packing plants in Chowan County for processing the catch.

In the very early days and later, into the 20th century, the greater part of the catch was sold to farmers and families in the Albemarle. They bought directly on the beaches and hauled the fish away in their carts to feed their families during the coming year.

Once used as currency, well into the twentieth century, cured herring, boiled, fried or corned, was the main item on the family menu, along with cornbread, sweet potatoes, bacon and yaupon tea. Herring were cheap and plentiful and some families ate them three times a day.

Said Virginia planter William Byrd, Provisions here are extremely cheap and extremely good, so that People may live plentifully at traffleing expense. Nothing is dear but Law, Physick, and strong drink.

Observed a historian in 1880, A dollar a month would procure for a person the most usual diet of much of the population. This source of cheap food, taken in connection with the mild climate, meant that a person could exist with very little work.

At the height of the fisheries industry, in the late 1800s, cured (salted) herring was shipped all over the world. The Capehart Fishery in Bertie County and Wood’s family Fishery in Chowan County were two large enterprises.

If you meander the byways skirting the east and west banks of the river, you can discover vestiges of the fisheries’ heritage. The remains of old fishpacking houses hug the shores, sharing swampy waters with tupelo and cypress.

Herring was king on the Chowan River, and the Chowan River was undisputed capital of the fresh water herring fishery. Even in the 1950s, fisheries at Colerain processed over 12 million herring a year, a steep reduction from former numbers but still impressive.

But the high times were not to last. Eventually, the Greenfield fishery was one of only a handful of fisheries left, a relic from bygone years.

Visitors traveled long distances to buy a keg or two of salt herring and stayed to watch black fishermen working the seines and women and children cleaning the fish. Sometimes their children and grandchildren would come along for a look at a piece of the past.

Troubled Waters

1972 was the breaking point.

That was the year Congress passed the Clean Water Act.

It was also the year algal blooms smothered most of the Chowan River from Holiday Island to Albemarle Sound.

Wind tides sometimes concentrated masses of algae until the scum looked like thick green paint.

When the plants died they formed floating mats that were joined by slime bacteria, and foul odors permeated life on the river.

Massive fish kills lined the shores. Fishing ceased. The summer-long event stunned citizens and government agencies.

This is a story that needs to be told. Very few people had foreseen an end to the mighty herring runs. It is the tale of how an extravagant gift from Nature was squandered. Of how people thought they could bring it back.

The first modest land-clearing by settlers barely affected land and water.

But population and fortunes grew, took natural resources from land and water, and spilled silt and chemicals into the river. One way or another, primeval forests and ancient swamps were eaten away and the waters poisoned.

By the 1970’s towns and schools, laundromats and shopping centers, lumber and paper companies, and dye and fertilizer industries were dumping their wastes into streams and creeks that fed the river. All told, there were 168 known Virginia and North Carolina point-source dischargers (pipes) into the river basin.

Farms, or non-point sources of run-off, were even greater threats to clean water in rural areas like the Albemarle. Detective work revealed that nitrogen and phosphorus, fertilizers used in agriculture, were running off farms and poisoning water.

After World War II more petrochemicals began to be used by farmers as fertilizers and pesticides. Photo by Pesticide Action Network

The Chowan River had the dubious distinction of being the first in North Carolina to suffer from eutrophication, or super-enrichment of water that can cause algae blooms and reduce dissolved oxygen until fish kills occur. But putting a name to the problem does not solve it.

The state concluded a 1972 study with a solemn message: Rigid enforcement of a comprehensive water management plan…is vitally needed if coastal waters. . . are to remain an asset…”

No action was taken.

Algae blooms continued each summer.

Fisheries declined. Feisty, hefty, striped bass that pumped up the economy, sought by both commercial and sport fishermen, became elusive. Harvest declined by 80 per cent because larvae were not surviving in traditional nursery areas.

River herring no longer spawned successfully. It was easy to blame overfishing on the high seas by foreign vessels, but even after ocean catches were limited, landings in the Chowan did not increase.

Blue green algae was smothering larvae and altering the natural food chain so young fish could not survive. Catches were down from close to a million a day a century earlier to 4-1/2 million annually by the late 1970s.

White perch suffered red-sore disease. Harvests plummeted. Each year, more and more fishermen cast aside their lifelong vocation to seek more profitable pursuits.

Fishing advisories were posted along the river because of dioxin released by paper production in Virginia.

Concerned citizens in Arrowhead Beach formed a Water Resources Committee to tackle the health of the river.

In 1978 the blooms lasted from June to November and extended from Holiday Island to Edenton Bay and out into Albemarle Sound. Over forty square miles of river and sound were blanketed with algae.

Spurred by citizen pressure, the state worked with Virginia to manage the river. Municipalities were asked to reduce sewage discharge and eventually, most installed spray irrigation systems on land.

Three industries discharged their wastes into the river system: United Piece Dye Works and CF Industries directly into the Chowan, and Union Camp Paper Corp into Virginia’s Blackwater River. For varying reasons they would eventually close.

Corporations are automatically labeled the bad guys in environmental disasters, but let’s take a closer look at one particular company. Union Camp, with century-deep roots in the community of Franklin VA, proved the exception. The company worked hard to become a good citizen of the river and its efforts should be recognized. It designed

- state-of-the-art holding ponds for sludge

- oxygenated its wastewater

- discharged waste only in periods of high river flows

- switched to ozone for bleaching of wood fibers to eliminate dioxin from waste

Finally, in 1979, came a hopeful sign. The Chowan River was designated Nutrient Sensitive Waters. Optimism grew. Now there would be some legal teeth to the wearying task of saving a river, with Special Order authority over anyone violating river standards.

Crushing disappointment followed quickly. That same year the NC General Assembly passed legislation exempting agriculture from any Special Order. . .

. . .despite agriculture’s contribution of 70 per cent of nitrogen and phosphorus run-off and copious amounts of sediment to the river.

CF Industries’ fertilizer plant in Tunis became the true bad guy in the group. Claiming that its business was agriculturally related, it released large quantities of nitrates that triggered algae blooms. The defunct plant is on the EPA Superfund List, with sealed holding ponds.

In 1982, a full ten years after the first terrible algae bloom, the state published a Chowan/Albemarle Action Plan. Phosphorus and nitrogen run-off should be reduced by a whopping 30 to 40 percent for the former, 15 to 25 percent for the latter.

They may look idyllic, but if not properly managed, farm fields lose silt and fertilizer in run-off into ditches, creeks, and rivers

In response, the NC General Assembly approved and partially funded BMPs.

Best Management Practices are really a set of common-sense techniques to protect rivers and streams.

- Planting crops without heavy tilling

- Using cover crops to keep soil in place.

- Grassing waterways and field borders.

- Rotating crops.

- Installing mini-dams to regulate water flow.

But BMPs were a tiger with no teeth. They were voluntary.

It took years to convince farmers to invest time and money in BMPs, even though they increased crop yields and saved on chemicals, and the state contributed funding.

More studies, more grants. The Albemarle-Pamlico Estuarine Study (APES), was part of a federal program to revitalize ailing estuaries.

Its research and field work contributed to protecting the river and wetlands. Its energetic public education program heightened understanding of the issues.

It became clear that only with the cooperation of agriculture and industry, local and state governments, and committed citizens could the river come back to life. Conditions have greatly improved.

But it was too little too late for the tiny but mighty river herring.

Fast food and supermarket quick-buys have taken the place of cured herring and scratch cornbread on the dinner table. The loss of this magnificent catch went mostly unnoticed except by bigger fish that fed on herring. And the fishermen who once made their living on the river.

By 2006 the herring fishery on the Chowan River was dead, collateral damage of progress.

Legacy

And what of the twenty-first century?

Counties and towns are looking for ways to support their economy without losing touch with their history or sacrificing small-town rural heritage.

Eco-tourism is bringing visitors who want to escape crowds and enjoy the tranquillity and remoteness of the Albemarle, its special history and environment.

Merchants Millpond State Park in Gates County is an example of landscape reclaimed from commercial use. It is a crown jewel in eastern North Carolina, an enchanted forest.

In the early 1800s Bennetts Creek was dammed to create the 760-acre millpond that would become a profitable hub for trade and industry. Gristmill, sawmill, and farm supply store, all owned by local merchants, hummed with profits. A century later, sometime before World War II, merchants sold their lots to developers.

Aerial view of water flowing from the Millpond into Bennetts Creek, then to the Chowan River. Photo by Jared Lloyd

During the heyday of post-war progress, the landscape could have been lost forever. But in 1960 A. B. Coleman donated 919 acres, including the millpond, to the state. This began the passage to preservation.

This wilderness wonderland is now a 3500-acre state park, with a dramatic mix of millpond, swamp forest and upland woods. Massive bald cypress and tupelo laced with Spanish moss tower over the millpond that is home to bald eagles and pileated woodpeckers, warblers and waterfowl. It is a sanctuary for visitors, too, as they drift along dark waters in kayak or canoe.

In remote Lassiter Swamp, which feeds the pond, some cypress trees are over 1000 years old. There’s always a fisherman on the pond and the great blue heron acts as sentinel. Ten miles of paths beckon hikers and picnickers with views of the pond. Campers can backpack or paddle to wilderness sites or motor into secluded wooded sites.

Alligators, too, enjoy the Millpond. Here, loafing on the water with friends. Photo by Chuck Richardson

It is a remarkable success story.

The history of the Chowan River and other Albemarle waters reflects the history of America: initial awe of a new land, exuberant speculative growth, squandering of natural resources, and unlimited progress assumed. Until the environment gives way.

Lessons learned. Energies redirected. Conservation ongoing.

While herring may be hard to find in the Chowan River, coalitions of citizens, public officials, industry, conservation groups and scientists have been engaged in thoughtful planning to conserve this special environment for future generations to enjoy.

Greg Hager’s artwork depicting the historic Roanoke River Lighthouse now situated in Edenton Bay gives eloquent tribute to the role that hands-on history can play in helping people appreciate the past. The unique lighthouse, its pilings screwed into the substrate to stabilize it in storms, operated from 1886 to 1941 at the mouth of the nearby Roanoke River. Today it can be toured by visitors.

(For more specifics about the Albemarle region, see Voyage Through Centuries, listed in sidebar.)